Walled City of Manah 16 April 2004

Walled City of Manah 16 April 2004

by Brien Holmes

When Geoff started putting together the plans for this year's trip to Nizwa, he began looking around for a new site to visit. While the multi-storey mud buildings of Hamra, the ruins at Tanuf, the Eden-like character of Misfah each continue to have appeal, there are so many other interesting sites in the Nizwa area that the search began.

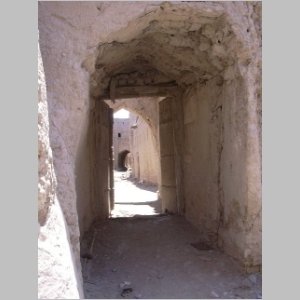

It didn't take long for the name of Manah to stop popping up in the literature. This amazing city, now abandoned, has a long history and some unique architectural features. The double defensive wall around the original community remains largely intact and is rare in such old sites. The mosques of Manah have attracted considerable attention owing to their design and the caligraphy around the mihrab.

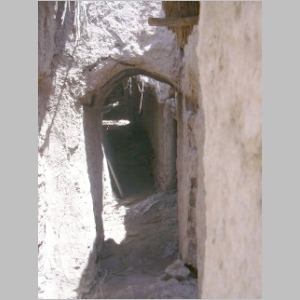

It is such a fascinating community -- there are references to caves in the vicinity of Manah, caves that were once used as shelter and hiding places during fighting -- that the city's street design and buildings have been the subject of special studies by faculty and students from the University of Liverpool. (Click here.)

The city was also the focus of discussions at the "German and International Research on Oman: Conference - Bonn (Germany), 2-3 July 1999".

Below are extracts from one of the most interesting papers from the University of Liverpool, School of Architecture and Building Engineering, on Manah. Click here to see an edited webpage version of the report.

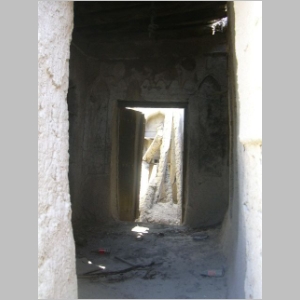

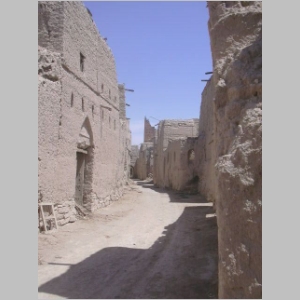

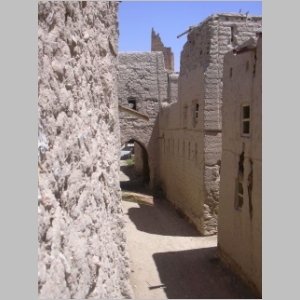

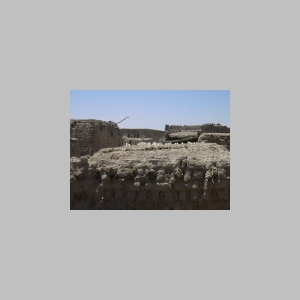

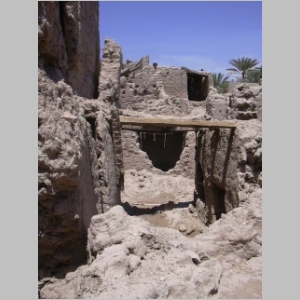

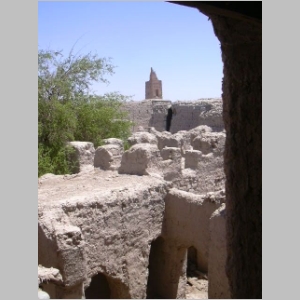

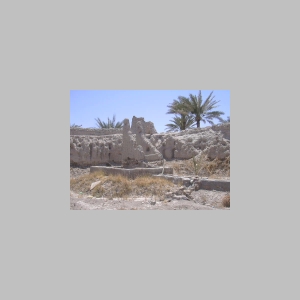

"Bilad Manah has remained deserted for approximately twenty-five years, partly due to practical but also political reasons; over the last ten years the deterioration of the settlement fabric has been extremely alarming. A similar fate has befallen the other constituent towns of the oasis, leading towards not only a gradual erasure of her town configuration and architecture, but also of a major section of Omani cultural history. Modern planned settlements and administrative facilities have been established beyond the eastern edge of the oasis. In this context of cultural prominence, desertion and dilapidation, the present study assumes added importance; the speculative modelling of the likely impact of historical events on settlement evolution, especially those related to tribal movement, could be considered the first step in the preservation of this unique settlement. Although popular stories hint at the establishment of a settlement by the Fars (Persians) around 531-579 AD, it is certain that the combined Halfayn-Kalbu wadi system was settled as early as the 2500-2000 BC. A developed oasis settlement would likely to have existed in the 6th century BC. This older form of oasis settlement, primarily an agricultural and commercial centre, straddled the developing trade routes on the desert periphery and had a symbiotic relationship with industrial (mainly copper producing) settlements. The settlements and the oasis depended on the perennial surface flow in the wadi-s supplemented by natural springs ('ayn) and wells. From these early days of habitation in the desert foreland, the springs were held in sacred esteem and became the focus of the settlement.

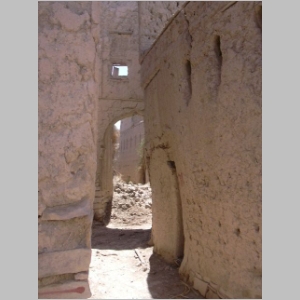

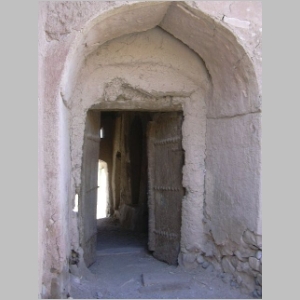

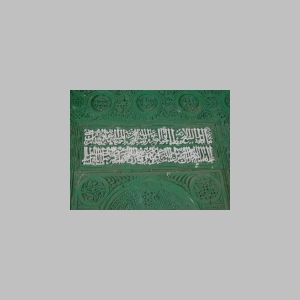

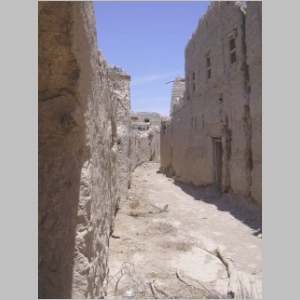

The orientation of the early rectangular walled settlement, as well as the principal north-south street, followed the natural gradient and culminated at the spring. Introduction of Islam (7th century) saw the pre-Islamic sacred center turned into a mosque (Masjid al-'Ayn) and the addition of two more (al-Shara and al-'Ali) on the main street. The decorated mihrab-s followed in the early 16th century. Towards the end of the Ya'ariba period (mid-18th century), the walled settlement of Manah underwent a significant extension.

There were no less than twenty tribal groups residing within the settlement around the time of its desertion. Different tribal groups may have gained importance at various times as a result of important socio-political changes taking place within the region. Although the majority belonged to the Hinawi political moiety, there were elements of the Ghafiri faction present within the settlement. The spatial and social exclusion or segregation of the three bayasira groups, the Sawaqi, Araini and Haddadi, into distinct housing clusters, was particularly interesting. Attached to various Arab clans in a client status, these groups were commonly thought not to possess a true Arab origin (asl).

Other sources discuss the mosques of Manah.

"The inscriptions in the mosques of Manah (Sultanate of Oman) In the XVI century in the village of Manah, Sultanate of Oman, there was a school of plaster-engravers, whose engraved mihrabs can be found in many towns in the area: Nizwa, Bahla', Adam, Suma'il, Nakhal, etc. Many of these mihrabs have also inscriptions. Just in Manah we can find four mosques with their "inscripted" mihrabs, of a good artistical quality in contrast with the sobriety of the ibadi mosque. Among these, the Great Mosque lies ouside the ancient walls of the city; the others: masgid al-'Ayn, masgid al-Surah and masgid al-'Ali, are within the walls. All the mihrabs of these three mosques are by the naqqas 'Abd Allah al-Humaymi, one of the most important engravers of that time. The inscriptions hand down to posterity the names of pious people who promoted the construction of the mihrab, some Coran (sic) verses and the name of the engraver.

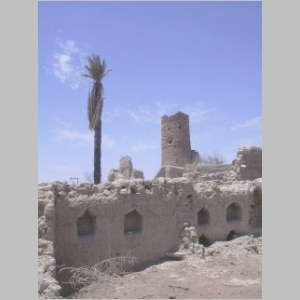

The remains we see today of the old fortified town of Manah are the remains of a city believed to have been established during the invasion of the Sassanid King, Khusrau Anurshirwan, in the 6th century.

Historical evidences show that this was the first spot where Malek Bin Faham Al Azdi, before the Arabs entered Oman following the collapse of the Mareb Dam in Yemen. (Click here.)

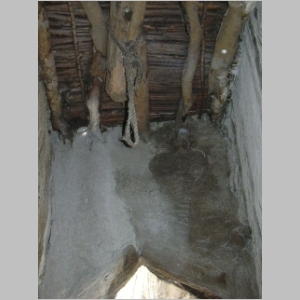

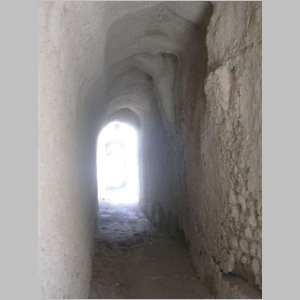

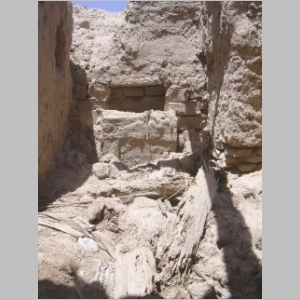

Elsewhere in the Wilaya of Manah, there are some huge caves which were said to be used as shelters during the wars. In Manah itself, there are underground caverns, visible where the roof of these chambers have collapsed.

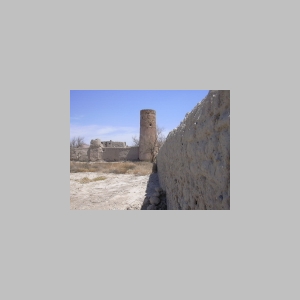

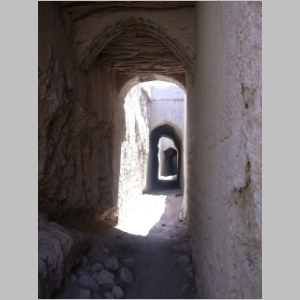

Visiting the city today, one is immediately impressed by the towers surrounding the site. Most are the round watchtowers that seem to be everywhere in Oman. However, at the main entrance to the walled city, there is a tall rectangular tower that resembles architecture from Yemen.

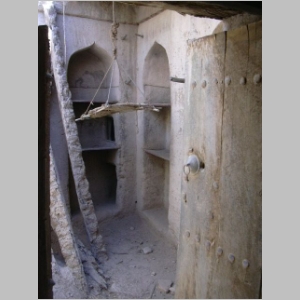

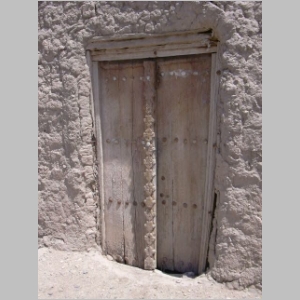

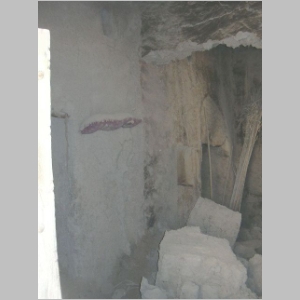

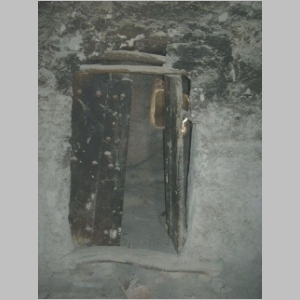

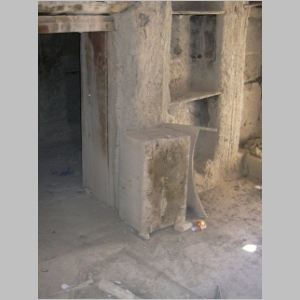

The features of the buildings of Manah are typical of those found in houses used during the past several hundred years. Alcoves in the walls are plentiful, some small, others almost floor-to-ceiling with shelves. Majlis rooms are not obvious as they are in traditional houses in the northern emirates, but the combination of family rooms connecting to a central room are common.

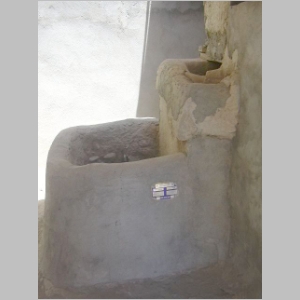

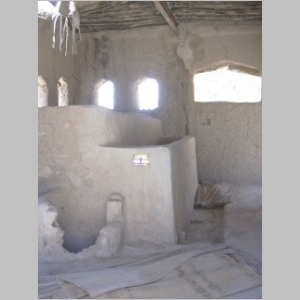

Water was collected from wells that are dotted around the city, almost all with a modern aluminum plaque attached by the Oman government which has been busy cataloguing water resources in the country. Visitors must be cautious as many of the very deep wells are not protected by walls. In the garden area of the walled city, the remains of an oxen-driven well are still visible, the oxen now replaced by a messy diesel pump.

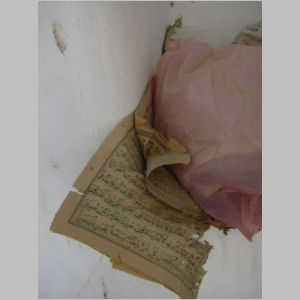

Littering the site are countless broken storage jars, metal kitchen items, storage boxes, various items of palm matting and personal items.

Residential fauna seem to consist of a pair of dogs that greet visitors warily and a large population of mouse-tailed bats.