Newsletter November 1998 No. 184

Newsletter November 1998 No. 184

Contents

- A fish suq in the desert of the United Arab Emirates

- Desert treasures: Jebel Hafit fossils

- Plant tours of recycling operations possible

- ‘Extinct’ buzzard re-appears

- Darwin’s letters, book online!

- Web Sites for ENHG types

- Oil damage assessment proposals presented by ERWDA

- Our desert creatures: The Amphisbaenid

A fish suq in the desert of the United Arab Emirates

by Philip IddisonI had been making regular visits to the fish market in the centre of Al Ain in the United Arab Emirates for some time before I queried the origins of a well established fresh fish market in this small desert city.

My trips were both to purchase food and also to research what food was available. The variety and abundance of fish throughout the year was striking and the vitality of the market confirmed a well established demand for fish from Al Ain residents. Whilst this could be expected from those sections of the expatriate populace who had a strong seafood element in their own ethnic cooking, Filipinos and Keralans for example, the observed popularity of fish for the nationals of the UAE was more obscure.

Was it a development of recent years with improved transportation, relative abundance and low cost or was there a historical origin for this taste? One clue was the existence of a few dried fish traders who seemed to do relatively little business. Perhaps this indicated a redundant commodity whose taste was no longer appreciated.

Until the late 1960's, Al Ain was an isolated date palm oasis with a small resident population controlled by the semi-nomadic bedouin of the Beni Yas confederation. The leaders of these tribes had gained control of the oasis by steadily purchasing date palm gardens. The Beni Yas had their main seat of power in the coastal settlement at Abu Dhabi, west of Al Ain, and were the most important tribe in a group of oases in the Liwa area to the south west of Al Ain.

Adjacent to the five villages comprising Al Ain are four Omani villages forming the Buraimi part of the oasis. In distance terms the Batinah coast of Oman is as near to Al Ain as the Gulf coast. There are strong cultural ties between the two communities although the strength of tribal custom has ensured that they now belong to separate countries.

The journey of 160 kilometres from Al Ain to Abu Dhabi took a minimum of 3 days by camel and could take as long as 14 days for a caravan of goods. Even two days were required once the Landrover had become available. The journey to Batinah is equally difficult involving passage through the Hajar mountains along Wadi Jizzi. Until the construction of the modern road system in the late 1960’s fresh fish was out of the question in Al Ain.

Economic Basis of LifeResearch into people’s past means of sustenance in the Trucial States revealed that my conception of purely desert based nomads needed to be broadened and that the resources of the sea had a more important role in the national livelihood than I had expected.

The main economic activities to sustain the lives of the national population of the Trucial States in the early part of this century can be divided into two groups. On one hand there were subsistence occupations: nomadic camel herding; tending date gardens and associated agriculture in the oases; sheep and goat herding where pasture and water supplies permitted; and fishing and fish drying.

Alternatively there were a limited number of trades:

- providing land transport by camel;

- pearl diving and trading;

- trading including overseas dhow journeys; and

- activities such as charcoal burning, firewood collection, guarding and crafts such as blacksmith, dhow builder.

Many families used several of these means of support to provide a living for their family. Thus it was not unusual for a nomadic herdsman with a small palm garden in Liwa to leave his family during the date harvest whilst he spent part of the summer fishing on the coast.

With 540 kilometres of coastline and abundant fish resources, fishing provided a valuable subsistence resource with the potential to generate cash or barter benefits. In 1969 it was estimated that 17% of the population were wholly or partly dependent on fishing for their support and cash income. During the 1950’s and 60’s annual production was estimated to be 10,000 tons of which 6,000 tons were exported.

The Gulf waters of the western UAE coast are rich in fish varieties particularly during the winter months when shoals of pelagic fish such as tuna, sardine and anchovy enter from the Gulf of Oman to reinforce the resident fish populations. The UAE has a shorter eastern coast bordering the Gulf of Oman which hosts an even richer sea fauna from the adjacent Indian Ocean.

Current production is about 90,000 tonnes per annum and a substantial proportion is consumed in the UAE. There were 4,464 fishing boats in 1996 and there is a growing awareness of the value and potential fragility of this resource.

An account of life in Al Ain and Abu Dhabi in the 1950's and 60's details a hardy lifestyle. Extended families usually had establishments in both towns with a corresponding split of economic support activities, pearl diving, fishing and trading in Abu Dhabi; herding, date gardens and seasonal cultivation in Al Ain.

Fishing along the Abu Dhabi coast was substantial and of prime economic importance. The fishing rights were held by the ruling sheikh who usually licensed them out. Fish was a dietary mainstay along the coast due to ready availability. In Dubai rice and fish were the standard midday food, in the hot climate there was a traditional taboo against eating fresh fish later in the day. Dried fish preparation was an important industry and supplied the inland areas with food and fertilizer as well as being an export commodity. There was a separate dried fish suq in Dubai.

A variety of fishing techniques were used including traps, gargour and dubeyer, and lines and nets used either inshore or from small sailing boats, sambuk and jalbut (derived from the English naval term jolly boat).

The techniques were sophisticated, making good use of both fixed and cast nets. Fixed nets exploited the natural topography, currents and fish migration routes. Such nets, hadra and sakar are still in use along the gulf shoreline. They extend out from the shore and catch fish as they travel with the longshore drift, collecting the catch in a small trap at the end of the net which needs only to be attended at low tide to collect the catch.

Fish could be kept for short periods in the gargour traps if these were weighted down offshore, thus preserving the catch for later consumption.

(Continued in next issue.)

Return to top of page

Desert treasures: Jebel Hafit fossils

At the foot of Jebel Hafit, near where the road from the cement works passes through a man-made gorge, numerous fossils of Nummulites, almost the size of a bottle-top, can be found. With them, lying loose on the scree slopes, are fragments of branching corals, oysters and gastropods, rare sea urchins and, even rarer, remains of barnacles and crab claws. At the northern part of the jebel north towards Al Ain, south of the Khalid bin Sultan road, eroded flanks of the anticline are exposed in the wadi. Here very hard, massive limestones are preserved with their beds in a near vertical position. Numerous coral "heads" are found here, some quite large about 60 centimetres in diameter.

Return to top of page

Plant tours of recycling operations possible

Those interested in protecting our environment may be interested in organizing a tour of the operations of two Dubai firms which have launched recycling programs.

Union Paper Mills and Al Jazir Glass Factory are both willing to give guided tours of their factories and recycling processes, environment officer Dianne Barber-Riley reports. At present, glass collection is only taking place in Dubai.

Here in Al Ain, Coca Cola has set up a collection site for aluminium cans in Sanaiya.

Return to top of page

‘Extinct’ buzzard re-appears

A Great Bustard, which has been extinct in Britain since pre-Victorian times, has been spotted in Dorset.

Otis tarda, the world’s heaviest flying bird, was spotted by two men at Broadstone golf course near Poole and then by a farmer near by.

The presence of the imposing bird, which is the size of a turkey, has excited birwatchers. Chris Mead, a consultant to the British Trust for Ornithology, said, “This bird became extinct several decades before the great auk died and one normally has to travel across Europe to see them.

“Great bustards were once a common sight in part of Britain. But their sheer size and conspicuousness made them an easy target for the sporting guns directed against them, and they died out some time around 1832.”

There have been only a handful of recorded sightings of great bustards this century. One was spotted in Felixstowe in February, 1987, and before that on Fair Isle in January, 1970. Recent bids to reintroduce them have been put on hold after years of unsuccessful attempts at breeding them in captivity.

In Western Europe, the huge and colourful great bustards breed in the dry inland areas of Spain and Portugal. But these birds do not migrate and the Dorset specimen will be from Central Europe. Reprinted without permission from the Daily Times.

Return to top of page

Darwin’s letters, book online!

New Scientist’s Darwinian Selection offered the following advice in a recent issue:

“You really should start with the founding father himself: persevere with On the Origin of Species (online at www.literature.org/Works/Charles-Darwin/origin/), enjoy Darwin’s Letters edited by Frederick Burckhardt or try Paul Ekman’s edition of The Expression of Emotion in Animals and Humans.

“If you’re feeling more modern, head for the Darwin Cafe at psych.lmu.edu/darwin.ht or try evolution.humb.univie.ac.at/jump/html for a roundup of web sites, journals and discussion groups.”

Return to top of page

Web Sites for ENHG types

Do you a web site to share with other ENHG members? If so, please contact the Newsletter editor at sbholmes@emirates.net.ae to be included in this list.

- Looking for an interesting science project? Check out the plans for a solar-power barbecue here.

- Ancient World’s web site for those interested in archaeology.

- Another good site for the amateur archaeologist. This site features a different dig each month.

- Disappointed in the recent meteor shower? Lots of stars here!

- And if you are interested in the search for extra terrestrail intelligence, this site is the home of SETI, an international band of radio and radio astronomy enthusiasts, based in New Jerysey, looking for signs of intelligent life.

- Spectacular images from under the microscope!

- Unmagnified photographs of a range of large crystals in all their incredible variety.

- Home of the New Scientist magazine. Latest issue available on line, with many links.

- Click on the ‘Arts and Culture’ option and you’ll find everything from the Ajman Museum to The World Arabian Horse Organisation here. The Ajman site may not equal Sharjah’s but worth a visit.

Return to top of page

Oil damage assessment proposals presented by ERWDA

Researchers from the Environmental Research and Wildlife Development Agency (ERWDA) suggest an approach to the assessment of oil spill damages to marine resources in the region.

ERWDA researchers are increasingly concerned about the threats caused by the exploitation of large oil fields, combined with extensive urban and industrial development, to the region's valuable natural marine environment. As a result, collaboration is being forged between ERWDA, the Regional Organisation for the Protection of the Marine Environment (ROPME) and the Kuwaiti Institute for Scientific Research (KISR). They are co-operating in an attempt to come up with an easily accomplished scientific method for the assessment of pollution, and in particular oil spill damages, in the Arabian Gulf and part of the Gulf of Oman, known as the ROPME Sea Area (RSA). Such an approach would act as a deterrent to those polluting and spilling oil and thus help to safeguard the region's valuable marine resources.

Links between the organisations began at the GCC - EU 'Oil pollution in the marine environment' workshop held in Kuwait City (2-4 Nov.’98) and was attended by over 50 participants. ERWDA's representative was Dr. Walter Pearson, the Director of the Agency's Marine and Environmental Research Center. Dr. Pearson has immense experience in the area of oil spill damages assessment as he was the Technical Leader of a large multi-disciplinary study to assess the damages to herring fisheries resources following the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska and was called as the expert witness for the trial. He also led a fisheries resource damage assessment team for the Seki oil spill, to the UAE, in 1994.

ROPME is hoping to develop an oil spill damage assessment procedure in the coming year. Dr. Pearson put forward an approach for the assessment of oil spill damages at the workshop, called the 'Compensation Schedule', which is now under consideration for adoption by ROPME.

“Oil spills are of major concern because more than half the oil transported through the global marine environment travels through the Gulf,” said Dr. Saif Al Ghais, ERWDA's Secretary General. “Several oil spills have already occurred in UAE waters and in those of other Gulf States. We look forward to working with ROPME, KISR, as well as the UAE oil companies, to create a scheme that will ensure that oil spills are dealt with in a well-planned and well-managed way.”

Dr. Al Ghais co-authored the paper which was presented by Dr. Pearson.

“The major problem is that often oil spill damages are not properly assessed because of the time and cost of the research studies needed,” Dr. Pearson said. “The Compensation Schedule approach translates oil contamination and resource exposure and injuries into economic damages. This has major advantages in that the schedule provides certainty to all the parties involved: the spiller, the responder, the resource trustee, and the insurer. Secondly, the approach is based on scientific knowledge and principles even when the available data is incomplete or uncertain.”

“It is essential that a scheme for rapid calculations of damages, without large or time-consuming studies, is established to allow frequent and widespread use,” Dr. Al Ghais explained. “This would enhance its value as a deterrent to those that pay less than full attention to oil spill prevention. Such a scheme should preferably be implemented throughout the ROPME Sea Area for the sake of the marine environment and the people who reply on its resources.”

Return to top of page

Our desert creatures: The Amphisbaenid

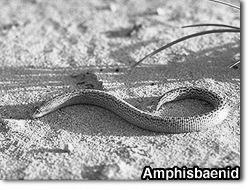

One reptile-like animal that is neither snake nor lizard, is the amphisbaenid (Diplometopon zarudni). Its short stocky body grows to approximately 20 cms in length. Much stronger than the thread snake and equipped with a spade-like snout, it is able to burrow in fairly compacted soil but is very rarely seen, since it is nocturnal and spends most of its time underground. Completely harmless, it feeds on insects which it hunts mainly underground, leaving a clearly visible raised trail on the surface. It is pinkish to purple in colour, dotted with small black spots and squares.

Return to top of page