Field Trip to Haywan 26 September 2003

Field Trip to Haywan 26 September 2003

A half a dozen vehicles, packed with members, headed for the foothills of the Hajar Mountains on the morning of Friday 26 September to visit some of the smaller settlements between Musah and Aboul

The first stop was the oasis at Haywan, located east of Musah (turn off the gravel track before entering Musah). (Ed note: when this report was first published, we were under the impression we were visiting the community of Afrathe. It was discovered later that Afrathe is the community near the paved road, where we turn to drive along the gravel track, while the oasis with the interesting water and stone is actually named Haywan)

Afrathe was once a much larger community given the size of the Islamic-style cemetery that dominated a small rise in front of the fields. There appeared to be more than 200 gravesites, including graves of adults and children, though there were no indications of recent burials.

Nearby, there was an assortment of terraced fields, only a few of which were under cultivation. The small collections of orchards, with the typical assortment of date palms, citrus (lemon, lime, orange) trees and mango trees, were scattered among the fields. The condition and size of the cultivated areas suggested that the volume of water in recent years had declined significantly, as has been the case at Aboul, for example, and may indicate a more saline water supply.

There were a number of interesting features in this settlement.

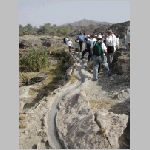

The irrigation channels were different from those observed in most mountain oases in that they were chiselled into the conglomerate and bedrock. The pattern of the channels suggests that workers, having discovered a damp section of ground, followed the moisture back to the point where the water emerged from the bedrock (spring). These water channels meandered across the surface and contained relatively small quantities of what appeared to be saline water, given the "crust" that appeared on the surface. Elsewhere in the oasis, more typical falaj systems, constructed of rocks and mud, were used to irrigate fields.

Members are accustomed to seeing limestone deposits on the mountains in the district but Afrathe featured limestone outcrops in and around the fields. Further study may indicate whether the limestone at Afrathe is of the same origin as the limestone on, for example, Jebel Abayl or "Jebel Mahdah". Limestone was used as a cement material for the falaj. There is even evidence, in some mountain oases, that workers learned to fire the limestone in makeshift kilns to make what is generally known as 'portland' cement today.

Afrathe also included at least two date drying platforms. In most mountain oases, these platforms, where harvested dates are left to ripen, converting starches to sugars, are made of gravel and are easily mistaken for makeshift mosques. At Afrathe, the drying platforms were made of mud that appeared to have been baked, probably a result of being laid down in a paste and allowed to harden in the heat of the summer sun. Further investigation could indicate if there were multiple layers of these platforms. The mud used was almost orange in color, compared to the dull gray mud normally seen in falaj construction and pottery.

The other feature Afrathe offered visitors was a collection of relatively large houses constructed of stone. The distinguishing feature was the pitched roof. In most mountain communities, especially those occupied in the past 100 years, most "houses" consisted of depressions in the surface, each depression lined with precisely placed small stones, usually to a depth of less than one meter. The stone walls extended about 20 cm above the surface and were reinforced with fine gravel. On top of these depressions, there was a pitched roof constructed using posts at each end with a central beam, against which palm branches or animal skins were laid. (Some of these houses are still visible near the road between Mahdah and Hatta.) At Afrathe, however, the end walls were constructed of stone, complete with a doorway and, in at least one building, a window. The end walls entended up and formed the support for a pitched roof, the end walls serving the function of the posts in the typical houses. This may have meant the houses had less through ventilation. There were at least four of these structures at Afrathe, in addition to perhaps a dozen of the typical mountain houses. Future field trips could include the precise measurement of these houses to add to the inventory of buildings.

The group drove east from Afrathe through abandoned communities and farms to a small cluster of a half a dozen houses, the name of the community not known. From here, the group drove directly towards the mountains, alongside a deep gorge carved into the gravel plain.

About half way between the houses and the end of the track, the remains of a copper smelter were found alongside the track. Only small fragments of the handmade bricks were still evident and the copper slag was minimal. There were also the remains of two cleared areas beside the track, their use and function unknown.

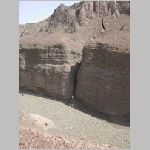

At the end of the track, the group investigated the deep gorge with many climbing down into the wadi. The vertical sides of the wadi were more than 20 meters tall and, as is typical of wadis in the foothills of the mountains, with bedrock on one side and an exposed face of conglomerate on the opposite side. On the top of the gravel plain, there were three structures, two of which appeared to be ancient houses. The group also spotted a small cluster of houses on top of the gravel plain on the opposite side of the wadi, about 200 meters "upstream". However, it was too hot to attempt a hike to the cluster. Perhaps later in the season these buildings could be visited to look for pottery and other clues of their age.

Thanks to Geoff for organizing the outing and to Brigitte Howarth and Sami el-Masri for sharing photographs.