Bulletin 18 - November 1982: The Natural History of Jebel Hafit

The Natural History of Jebel Hafit

(Editor's note: During the past few years, several members have climbed Hafit, some because it is there and others to survey its wildlife. A more systematic approach was made on February 5th and 6th 1982 when a small group climbed and camped overnight just beneath the summit. Unfortunately, the second day's survey was made impossible by drizzle and heavy cloud. However, sufficient data was collected on this and other visit to form the basis for this article. Contributors are Graham Tourney (the climb itself), J.N.B. (Bish) Brown (mammals and birds), Martin Willmot (animal traces), and Rob Western (vegetation). Graham was also responsible for determining the spot-heights based on the February trip. A presentation with slides on this subject was made to the Group in June.)

Introduction

Jebel Hafit is a large hill situated south of Al Ain, about 160kms east of Abu Dhabi town. It is a foreland anticline developed by gravity folding in response to the uplift of the Oman Mountains and extends for some 10kms in a north-south direction. From a distance it appears as a regular whaleback, but close-up the hill is deeply incised with wadis and eroded faces. The main mass is late Miocene but along the western flank are the remains of Oligocene reefs that once overlay the whole; these have been severely eroded and pale into insignificance beside the core of the hill, which itself is covered by a limestone mantle. The core is composed of calcareous mudstones and Eocene limestone, though further north in the environs of al Ain, marls are a dominant feature of the surface.

The climate is arid and the Jebel has a bare appearance due to its heavy eroded and steep flanks. Temperatures rise to a maximum of 45°C in June and July but the diurnal alternations can be wide. Rainfall is limited, with flash storms in spring and the occasional storms between July and September. Very little water is collected on the hill except in minor and temporary pools; most rainfall runs off extremely quickly and rapidly dissipates in the alluvial plains.

Because of its relative isolation and different geological character to the main mass of the Hajar range to the east, Hafit has a certain fascination. It is nearly 4000 feet high at the center and relatively unspoiled. That it attracted Neolithic man is evident in the large number of cairns especially on the northeast flanks. It is a quiet, rather awesome sight, still holding the spreading tentacles of Al Ain suburbs at bay. Naturalists can only greet plans for a tourist development on the summit with dismay and it was partly with this factor in mind that the Group has been so keen on exploring Hafit.

Climbing Jebel Hafit

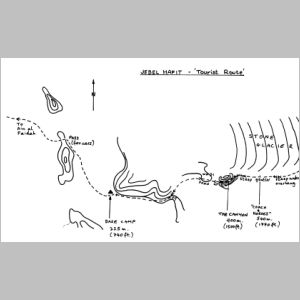

(The following notes set out the 'Tourist Route' climb. A description of the ascent route is covered followed by brief notes on the descent. A few general points such as timing and clothing then follow.)

The starting point for this route is not easy to find, even referring to the map. It is best to go up first with somebody who has been before. The route covers a horizontal distance of only 1.75 miles but involves climbing over 3000 feet. This represents an average gradient of 1:2.5, something akin to climbing the stairs in a house, but for nearly two miles! The summit height is about 3800 feet, and a reasonable time for the ascent is between two and four hours depending on fitness (and youth). The descent takes as long due to the tricky nature of the terrain.

The route climbs steeply immediately one leaves the wadi. It is very important not to go too quickly at this early stage and let the body become accustomed to the greater oxygen demand and faster heart beat. It is also better to keep going slowly and steadily rather than more speedily with frequent rests.

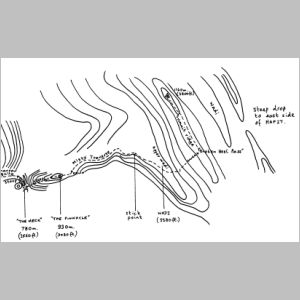

The first steep portion is soon negotiated and leads to a gently sloping 'hogsback' ridge. The route then descends into a wadi, one of the most scenic spots of the climb. The track ascends again through a very impressive canyon, the top of which marks the first 800 feet. Turning sharp right at this point, the route immediately steepens, but one is always out of the sun on this section, which works its way beneath a long overhang. There are several steps of five or six feet which involve proper rock scrambling, including hands, knees, elbows and the odd push or pull from a companion. To the left of this long section, just across a dividing narrow but deep wadi, is an open area of steeply faulted limestone nicknamed the 'Stone Glacier' which almost folds over upon itself at the upper end. At the top of this gully climb, one arrives at the 'Neck', at 2500 feet possibly the steepest part where great care must be taken not to dislodge rocks which could go bouncing down to injure a climber lower down.

After the 'Neck' comes the most exposed part of the trip to a huge rock pinnacle directly above and, although now in the sun, there is often a pleasant breeze. Beyond the pinnacle a short sharp descent is made before traversing around into a more open upper wadi. This is easy going and provides a welcome break before the short steep climb onto the summit ridge where a stroll takes one to the summit peak oneself for a well-earned rest and to record one's name in the climbers' book housed in a biscuit tin in a tiny cairn. On a clear day, the magnificent views across to the Oman mountains or west to the emptiness of the sands is worth it even for those with the most blistered feet. It is worth remembering, however, that the summit can be in cloud, or extremely windy; often rising sand around Hafit obscures any view of the ground below.

As mentioned earlier, the descent takes as long at the ascent, largely due to the steepness combined with loose stones and unstable boulders. Great care must be taken, particularly in the upper sections, and each footfall should be considered. The surface rocks are very sharp and rough and any small fall could easily result in serious cuts and abrasions. Remember that a twisted ankle on the upper sections will cause considerable problems for your companions as well as yourself.

Hints

It is quite possible to have pleasant conditions (cool and dry) in the winter months. It is not a good idea to attempt the climb between April and November; January or February is usually ideal. The best time to start the climb is before 7 a.m. to get the coolest part of the day, and hence camping in the vicinity the night before is an advantage. An absolute minimum of one bottle of water per person should be allowed, more if possible, since one or more bottles can always be deposited during the ascent for use on the return trip. Normal mineral bottles tend to crack easily, so carry the water in heave-plastic bottles.

Clothing should be light and loose, and cotton is preferred. Shorts are a personal choice, though long trousers offer more protection if one stumbles. A strong pair of gloves is very useful for the steeper sections to avoid grazed hands. But the most important item is footwear. Boots are best as they give protection to the ankle, but it is still vital to check exactly were one is placing one's feet. Stout shoes are acceptable, especially for the more experienced hill walkers, but they must be able to withstand the rigors of Hafit's abrasive surface.

Having mentioned heat, a provision should also be made for cold. A sudden rainstorm or arrival of a cold wind can reduce the temperature dramatically and it is worth taking a very light but windproof anorak or cagoulee. Even a large waste bin liner will keep a lot of dampness and chill out. During the February camp, a strong downpour and high winds were experienced at dawn just beneath the summit, and extra clothing was well worth its weight.

Mammals

During the February climb, we saw only a few tracks and some droppings to indicate the presence of animals. The noise made by five climbers gave them ample time to move to an undisturbed area or crevice.

A few footprints in the sandy area near the base of Hafit were almost certainly those of a Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes). Red foxes are fairly common in many parts of the United Arab Emirates and tend to be longer legged than the European version, have larger ears, and are more grayish in color. They probably subsist on small mammals, reptiles and the occasional bird. When near civilization, they will also scavenge around rubbish tips.

In several places, even near the summit, we came upon goat type droppings, but there were no sign of feral goats. After our climb the Al Ain Group reported that the body of an old dead Arabian Tahr (Hemitragus jayakari) had been found on the Jebel. Wilfred Thesiger recorded the existence of a small isolated population of this small goat in the 1950's. Future developments proposed for Jebel Hafit will put severe pressure on the survival of this unique animal, found only here in the UAE. There are small populations in Oman, which are now protected in a conservation area around Jebel Akhdar.

On a previous low level climb, we discovered several bats under ledges and in crevices but they flew away before we could make a positive identification; we did not see any bats on this occasion.

Several other species of animals have been recorded from around Jebel Hafit and the Al Ain area. The following is a list of mammals described in "Mammals in Arabia" by Dr. David L. Harrison, published by Ernest Benn Ltd.:

- Cape Hare (Lepus capensis omanensis)

- Lesser Jerboa (Jaculus jaculus)

- Baluchistan Gerbil (Berbillus nanus)

- Cheeseman's Gerbil (Gerbillus cheesmani)

- Wolf (Canis lepus)

- Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes arabica)

- Arabian Tahr (Heritragus jayakari)

- Brandt's Hedgehog (Parachinus hypomelas)

- Lesser Mouse-tailed Bat (Rhinopoma hardwickei muscatellum)

- Sheath-tailed Bat (Taphozous nudiventris)

- Persian Leaf-nosed Bat (Triaenops persicus)

- Trident Leaf-nosed Bat (Asellia tridens)

- Kuhl's Pipistrelle (Pipistrellus kuhli)

Birds

At base camp on the morning of the climb, a Great Gray Shrike (Lanius excubitor) was hunting around acacia trees. Known as the butcher bird from its habit of hanging prey on sharp thorns, it is known to be resident most of the year. Isabelline (Oenanthe isabellina) and Desert Wheatears (Oenanthe deserti) were also seen.

On the climb, a disused nest of a Pale Crag Martin was noticed under an overhanging ledge. Several martins were seen wheeling above us collecting insects. At the same point, four pigeon type birds flew out and disappeared round rocks before they could be positively identified. There was white on the rump so they could have been Rock Dove (Columba livia) or feral pigeons. At the summit, we had the exciting experience of seeing a large bird of prey at close quarters. From its long white neck, brown coloring and dark trailing edges to the wings, we concluded that it was a Griffon Vulture (Gyps fulvus). We shall have to make another trip to the top to confirm its identity as we have since been advised that the vultures in this area are a race of the Lappet-faced Vulture (Torgos tracheliotus).

Late in the evening, several Egyptian Vultures (Neophron percnopterus) were seen high in the sky. The distinctive black and white coloring stood out even against the darkening skies.

Next morning the low cloud and fog grounded all the birds and we saw very few on the way down.

Animal Traces

There were very few obvious animal traces on the route up the mountain, the surface being sandless and barren of soft spots were imprints could be made.

Fox: Several fox droppings were found on two separate ridges at about 1000 feet. Beetle wings were clearly visible in the droppings indicating at least part of the diet. Two fox tracks were identified and photographed in a tiny sand patch at 1700 feet alongside the 'Stone Glacier'.

Tahr: About a dozen dark red droppings shaped like, and the size of, pine seeds were found at about 1000 feet. Peter Dickinson, Curator of the Al Ain Zoo, has subsequently identified them as Tahr droppings. He also informed us that the body of an aged male Tahr was recovered from about this height on the western flank this summer. Sightings of this animal are extremely rare and it has only recently been established that they do, in fact, still exist on Hafit.

Hare and Goat: Droppings of these animals were commoner.

Birds' Roosts: During the climb we came across several examples of well-used roosts in rocky niches and overhangs but it was impossible to identify bird species.

Griffon Vulture nest: Though there may be some doubt as to whether this is a Griffon or subspecies of Lappet-faced Vulture, the nest on the summit is real enough. In 1981, a single chick was reared and this year the nest contained one egg, white, pointed at one end and as large as an ostrich egg. The nest is clearly used year after year, as evidenced both by its huge size and depth, and by the massive amount of debris beneath, including pellets containing the skulls and bones of small rodents and reptiles, presumably lizards. Larger bones, possibly of hare and birds, also lay scattered around.

The Vegetation

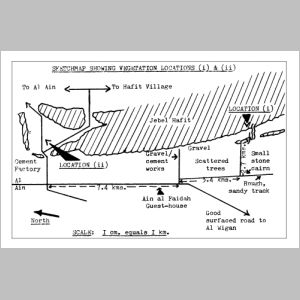

In 1980, '81 and '82, a number of minor expeditions were made to Hafit to record plants. The main locations surveyed were (i) an area on the west flank approximately 6kms to the southwest of Ain al Faidah Guest House (c. 24° 03' N, 55° 46' E) and (ii) the Wadi Tarabat which runs beside the Al Ain Cement Factory some 7 kms north-northeast of Ain al Faidah (c. 24° 08' N, 55° 45' E). The two locations are separate but related by the south-north extension of Hafit into the environs of Al Ain. Location (i) extends from the base of the west flank where a large wadi disgorges onto the alluvial plain, back to the summit of the Jebel. Location (ii) is southeast of the Cement Factory and comprises the bed of the wadi, its banks and the immediate surrounding plain. Other areas have been checked intermittently at varying times of the year and the overall vegetation patterns conform generally to the recordings at these two locations. The huge whaleback of Hafit, dripping down steeply on both sides, presents similar plant habitats on east and west flanks. The east side, however, is sparser because its slope is even more steeply defined.

The geology of location (i) is typical of the main mass of the Jebel, with its overlying limestone beds and shelf carbonates. The west flank is sharply incised with numerous narrow wadis that are quickly lost in the sand adjoining the alluvial plain that only extends for a maximum of three kilometers from the base of the hill. Overhangs and areas of scree are notable features and the vegetation tends to be patchy. Throughout most of the year, this area is very arid with only woody perennials in obvious evidence. However, the scene changes dramatically after the spring rains and in April and May, the area is a huge uneven mat of colorful ephermerals. There are usually odd storms in August and September, occasionally in October, but the general balance of vegetation cover is not altered.

Location (i) -- Perennials

At any time of the year, a number of perennial species may be seen. On the alluvial plain up to the base of the Jebel Acacia tortolis is the dominant tree, though just a little further out, on the gravel/dune overlap, there are patches of Prosopis spicigera, too. This latter tree is more rounded in form than the typically flat-topped acacia, which lends an African savanna appearance to the landscape.

In and along the banks of the normally dry wadis, the yellow-flowered panicles of the evergreen shrub Pulicaria glutinosa are very evident in January and February. This plant reaches a height of 70 cms and is locally dominant among stretches of tumbled boulders along with species of Tephrosia that produces numerous purple flowers on long branches from December on. The odd specimen of Cassia italica may be seen, but this prefers more stable sandy and gravel conditions.

At the foot of the Jebel, around 225-275 meters above sea level, scree slopes make climbing difficult, but the odd A. tortolis grows to five meters or so and provide a little temporary shade. Surprisingly, Ziziphus spina-christi does not appear to be represented on Hafit, the only other tree in this locality being Moringa peregrina. This species reaches heights of eight meters in the northern Emirates but here it has a maximum height of about four meters. M. peregrina is distinguished by its panicles of lilac-white flowers from February to April followed by gray woody pods up to 20cms long which split lengthwise into three revealing brown bean-sized seeds; these fruits make identification easy. Other perennials at this low altitude include Fagonia indica, a spinescent shrub with numerous solitary pink/mauve flowers in early spring and again in the autumn. The leaves are very small and each branch node has four curved spines. A few poor specimens of Hamada elegans, with tapering but erect branches formed by chains of fleshy leaves survive at this height but they are noticeably out of their normal environment when compared to the thriving bushes in the sand plains further west. Zygophyllum (qatarense?) plants are also common among the scree and boulders. The dominant perennial grasses here are Cymbopogon parkeri, Cenchrus ciliaris, and Aristida adscensionis.

One of the more showy perennial shrubs on lower rock faces is Capparis cartilaginea with its rounded leathery leaves often half-eaten away by larva of hawkmoths and other insects. This woody plant is stiffly spiny and grows up to four meters across as it straggles over rocks or hangs down cliff sides. It is at its most spectacular just after dawn on August mornings when the large white petals open out revealing red and pink stamens up to 6cms long. The flower closes up and wilts around 9 a.m. until next day. The fruit is a small green cucumber-shaped berry, sometimes rose-tipped.

Between 250 and 550 meters, odd specimens of Periploca aphylla may be found. This shrub can attain the proportions of a small twining tree in favored localities but it tends to be chewed up as a result most probably of the predations of flocks of feral goats. Its linear leaves are almost non-existent and the axillary cymes of lilac flowers (February-April) are also inconspicuous. It is more easily recognized by its fruit, a pair of follicles on a horizontal plane, each up to 12 cms long. The flower buds are sweet and may be eaten raw or cooked as a vegetable -- though this is definitely not recommended in view of the rarity of the species. Cruciferae are well represented on lower levels and include Physsorynchus chamaerapistrum, with its large, cabbage-like leaves and pale lilac or white flowers on long central stems. It is the nearest thing to an elongated wild cabbage in the AE, but very similar to Moricandia sinaica, from which it differs only in the longer fruit. M. sinacia may very well be present on Hafit, too.

As one approaches the top half of the Jebel, the slope becomes less precipitous with area of uneven rocky 'terraces' which allow for greater vegetation cover. Here may be found other woody perennials such as Ochradenus aucheri, a shrub that grows to larger proportions elsewhere in the lowlands of the country, but is rarely taller than 50cms on Hafit. Its clusters of spiky yellow flowers followed by fleshy green (turning yellow) berries are distinctive. The branches are spiny, characteristic of this species in an arid environment. Zilla spinosa is another Crucifer, also encountered on the lowlands, which turns spiny after the first year. The many flowers are pale lilac and the fruit is a warty green berry tapering to a pointed beak. Both of these last two species are found in the base of the fault on the summit that runs parallel to the main axis of the Jebel. The processes of erosion have formed a narrow twisting wadi in this fault, where the shrub Dodonea viscosa is also found, the largest of the summit plants, growing to two meters. The major component of perennial vegetation throughout the full elevation of Hafit, however, is Euphorbia larica, a cactus-like succulent with slender stems branching from the base. It is very common at the base of the Jebel, and well represented at any open patch from base to summit.

Location (i) -- Annuals

It is from mid- to late spring that ephemerals transform the landscape of Hafit, though this is only evident at close quarters, particularly at lower elevations. The Leguminosae family is particularly well represented. Indigofera arabica, a prostrate silver-green plant with tiny blood-red flowers, is fairly common in the lower wadi reaches, along with Hippocrepis constricta, which bears particularly contorted seed pods. Another is Argyrolobium roseum, distinguished by its trifoliate leaves, tiny yellow flowers and flattened curved legume. These are all small annuals, just a few inches high, and usually found in patches of sand among boulders.

Cruciferae are also abundant and include Morettia parviflora, Anastatica hierochuntica, Diplotaxis harra and Savignya parviflora. Of these, A. hierochuntica is very unusual in that the rather nondescript flowering plant (semi-prostrate, with minute white flowers often half-covered with sand) takes on a completely different aspect when the flowers and leaves drop off, the tiny stems turn woody and fold over inwards to enclose the numerous seeds as if in a clenched fist -- hence its name in Arabic which means 'hand of Miriam'. The plant thus resembles a miniature skeleton-like basket hugging the ground, awaiting the next rains, which will release the tension and open out the branches. This can be clearly demonstrated if a seed-bearing plant is collected in summer and put into a cup of water at home. New plants grow all around the old parent.

A very attractive annual is the pink-flowering Pseudogaillonia hymenostephana, which is rare on Hafit and found only in small clumps around rocks at the base. Arnebia hispidissima is more abundant in the same habitats, especially in years of abundant rainfall when it may dominate whole areas of open sand and gravel. It is much hairier but otherwise similar to its cousin A. decumbens which is commoner towards the Gulf coast.

The Caryophyllaceae Family is represented chiefly by Cometes surattensis and Sclerocephalus arabicus, two tiny, compact annuals that can be very common locally. The former changes from green to a fluffy brown or yellow as the season progresses, up to 5cms high and a maximum of 20cms across. It has a very short flowering season of three weeks or so.

One of the more unusual and spectacular plants is Boerhavia elegans, which is related to Bougainvillea. This species has been described as looking like 'puffs or red smoke' as its tiny red flower stalks are inconspicuous at a distance but stand out against the rock at close quarters. The basal rosette of green and purple tinged and veined leaves also makes this plant easy to identify, even when not in flower. It is found among the lower scree and wadis and grows up to 50cms tall.

Reseda aucheri is another ubiquitous annual at lower levels, distinguished by its narrow but long (up to 15cms) plantain-like yellow flower spikes. In favorable seasons, it appears that this species is not a true annual, but has a second flowering period in October/November and only dies back partially over winter. This plant is said to have a soothing effect on bruises, a useful tip for climbers.

Among annuals the Zygophyllaceae Family includes Tribulus macropterus, which is sometimes perennial though apparently not on Hafit. This has bright yellow 'buttercup' type flowers, which are auxiliary and terminal on long tailing stems. It can be distinguished from other Tribulus species by its fruit, which is roughly spherical with five broad and continuously dentate wings. It is found on lower levels and also on sand and gravel throughout the country.

Checklist for Location (i)

| Family | Species |

| Capparaceae | Capparis cartilaginea |

| Cleomaceae | Cleome aff. Rupicola |

| Cruciferae | Zilla spinosa Anastatica hirerochuntica Morettia parviflora Diplotaxis harra Physsorynchus chamaerapistrum (poss.) Moricandia sinaica Savignya parviflora |

| Resedaceae | Reseda aucheri Ochradenus aucheri |

| Cucurbitaceae | Citrullus colocynthis Cucumis prophetarum |

| Zygophyllaceae | Fagonia indica Tribulus macropterus Zygophyllum (qatarense?) |

| Euphorbiaceae | Euphorbia larica Chrozophora sp. (poss. Olivieri) |

| Rutaceae | Haplophyllum tuberculatum |

| Sapindaceae | Dodonaea viscosa |

| Urticaceae | Forsskahlia tenacissima |

| Polygonaceae | Rumex vesicarius |

| Caryophyllaceae | Cometes surattensis Sclerocephalus arabicus Silene villosa |

| Chenopodiaceae | Hamada elegans |

| Leguminosae | Acacia tortolis Prosopis spicigera Cassia italica Tephrosia sp. (poss. Apollinea) Indigofera arabica Argyrolobium roseum Hipporcrepis constricta |

| Asclepiadaceae | Periploca aphylla |

| Moringaceae | Moringa peregrina |

| Boraginaceae | Arnebia hispidissima Heliotropium sp. |

| Scrophulariaceae | Anticharis arabica |

| Nyctaginaceae | Boerhavia elegans |

| Compositae | Pulicaria glutinosa Rhanterium eppaposum |

| Liliaceae | Asphodelus tenuifolus |

| Gramineae | Cenchrus pennisetiformis Cenchrus ciliata Cymbopogon parkeri Aristida adscensionis Astenatherum forsskahlii Stopagrostis plumosa Dactyloctenium scindicum |

Location (ii)

In some ways, this is a more favorable habitat in that the wadi concerned is cut into a gravel plain, is wide, and not steep. In spite of sand-removing operations, its numerous side-bays and miniature promontories provide extensive vegetation cover. However, a glance at the checklist shows that this location favors a different type of vegetation, and that certain species are superbly adapted here just as other species are at Location (i).

Dotted around the plain are Acacia tortolis and, where sand has collected, the occasional Calotropis procera tree with its large leaves and flower panicles, while in gravelly side tributaries which have not yet cut noticeably into the plain, the dominant plants throughout the year are Pulicaria and Tephrosia (apollinea?). Again, it is late spring that show off the area at its best with a host of annuals. Anastatica hierochuntica, Farsetia ramosissium, Savignya parviflora and Eremobium aegyptiacum, all crucifers, can be found along the edges of the wadi base. The last-named has also been recorded in flower and fruit in October (1982). Within the confines of the wadi, Aerva javanica is a major vegetation component throughout the year. This plant grows up to a meter tall and is unmistakable with its woolly white racemes (often crowded with tiny insects). After rains, large areas of the bed are covered with the trailing branches of Citrullus colocynthis, up to five meters long. The leaves are extremely indented with tendrils, the many flowers are pale yellow and the fruit is an apple-sized gourd that turns from green to yellow when dry. These dry fruits become detached when the plant dies back and roll around in the wind, or are carried along in flash floods to colonize new areas. The gourd is poisonous and rarely touched by any creature except, apparently, the odd desert rodent.

The Leguminosae Family is well represented with Cassia italica abundant all year round, though particularly attractive in autumn with its numerous yellow flowers and characteristic brown flattened legumes. Others in this family include Indigofera arabica, Crotalaria aegyptiaca and Argyrolobium roseum. Reseda aucheri here is very common and appears to be perennial for much new growth is put out in October and November. Clumps of Haplophyllum tuberculatum, a plant up to 70cms tall with a strong and slightly offensive scent, are clearly visible in April and May among A. javanica rising above lesser annuals.

Among the more unusual plants is Ducrosia anethifolia, a tiny Umbelliferae that seems to be endemic only to this part of Hafit. It prefers the more gently sloping sand banks and thrives in spite of wind and erosion, though it is barely 5cms tall and up to only 10cms across. On the gravel plains adjoining the wadi can be found the annual Dipcadi erythreum, a tiny lily which is distinctive by its three-cupped fruit case, each cup holding three or four flattened black seeds.

Arnebia hispidissima covers the ground in spring, along with Silene villosa, Fagonia olivieri and Tribulus macropterus. F. olivieri looks rather like a small inverted pyramid, up to 30cms high, and its masses of tiny pink or purple flowers are very attractive close up. It is very spiny and unlike F. indica, its cousin at Location (i), its young twigs are square (not circular) in cross-section, though this difference is often difficult to determine in the field. Occasional bushes of the succulent Zygophyllum (qatarense?) are spread here and there on the wadi banks, interspersed with Hamada elegans. Cymbopogon parkeri and Stipagrostis plumosa are the commonest grasses.

Checklist for Location (ii)

| Family | Species |

| Cleomaceae | Cleome brachycarpa |

| Cruciferae | Anastatica hierochuntica Farsetia ramosissima Savignya parviflora Eremoblium aegyptiacum |

| Resedaceae | Reseda aucheri |

| Cucurbitaceae | Citrullus colocynthis |

| Zygophyllaceae | Seetzenia lanata Zygophyllum (qatarense?) Fagonia olivieri Tribulus macropterus |

| Rutaceae | Haplophyllum tuberculatum |

| Caryophyllaceae | Silene villosa Cometes surattensis |

| Chenopodiaceae | Hamada elegans |

| Leguminosae | Acacia tortolis Cassia italica Tephrosia sp. (poss. Apollinea) Indigofera arabica Crotalaria aegyptiaca Argyrolobium roseum |

| Amaranthaceae | Aerva javanica |

| Umbelliferae | Durosia anethifolia |

| Convolvulacease | Convolvulus virgatus |

| Boraginaceae | Arnebia hispidissima Heliotropium sp. |

| Compositae | Pulicaria glutinosa Ifloga spicata |

| Lilaceae | Dipcadi erythreum |

| Gramineae | Cymbopogon parkeri Stipagrostis pluosa Setaria verticillata Astenatherum forsskahlii |