Notes on the Evolution of a Traditional Cultural Sport

by Sulayman Khalaf

The following article appeared in the 1999

edition of Anthropos pp 85 -106

- Abstract

- 1. An Emiri Introduction

- From Camel to Truck

- From Truck to Camel Again

- Continuity and Change in Camel Racing

- 2. Modern Media Information Aspects

- 3. Organizational Development Aspects

- The Racetracks

- The Introduction of Different Races for Different Breeds

of hejin

- The Introduction of Different Distances for Various

Age-Groups

- Organization of Races According to Types of Owners

- Feeding and Management

- The Training of Racing Camels

- 4. The Economico-Political Aspects

- Salaries and Wages

- Selling and Buying Racing Camels

- Camel Markets

- Marketing and Advertising

- 5. The Politico-Cultural Aspects

- 6. Conclusion: Aspects of Local/Global Dynamics

- Footnotes

- References Cited

Abstract: The paper offers an ethnographic

documentation of camel racing as a growing traditional cultural heritage sport

in contemporary Gulf Arab societies. An integrated anthropological approach is

used in describing and analyzing the multiple aspects and functions of the races

as an evolving cultural revival within the broad contexts of oil wealth, the

building of modem nation-state, and modem global forces. Camel racing is

analyzed as an activity for distributing oil wealth among the Bedu segment of

the United Arab Emirates national population, as a significant component in the

enterprise of statecraft and state formation, and as cultural festivals for

preserving and promoting national cultural identity which appears threatened by

multiple global cultural flows and dynamics. [United Arab Emirates Society,

Bedouin culture in the Gulf; cultural revival, Middle Eastern popular culture

and oil, sociocultural change.

Sulayman Khalaf, M. A. (1975, American University of Beirut), Ph. D.

(1981, University of California, Los Angeles), Associate Prof. of Anthropology

at United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain. Publications: numerous articles (in

English, and Arabic) on tribal peasant communities in Syria, and on

sociocultural change in contemporary Gulf Arab societies.

Return to Index

The dawn of the great transformation in the Bedouin world is pictured for us

by the novelist Abdul Rahman Munif. One day a Bedouin Emir stood among his

fellow tribesmen of Wadi Al 'Uyoun in the Cities of Salt and said to them,

"Oh ya Ibn Rashed there are here under our own feet seas of oil, seas of

gold and al khaweya [the foreign brethren of the oil companies] have come

to dig out the oil and the gold" (Munif 1985: 87). The Emir went on to say,

"Oh people of Wadi Al 'Uyoun, you will be the richest and happiest of all

people, as if Allah sees nobody but you. You have been patient for long. Allah

is witness to that. But now you will be living a new life as if in a dream. You

will talk about your old days as if they were just stories to be told. You the

wise and senior men of Wadi Al 'Uyoun; your duty now is to facilitate the work

of our friends, and serve them with your very own eyes" (1985: 85).

Prior to the al khaweya (the foreign oil companies) uncapping the

great of oil reserves in the Gulf, the Bedu of Arabia fully utilized the camel

as "the technology" -- a la Julian Steward -- upon which they depended

for exploiting the meager and constantly changing givings of their desert

homeland. The Bedu perceived the pattern of their pastoral life as something

always changing. They viewed their world as precarious and unpredictable like

the changing clouds above them. This world view is captured in their saying,

"Ye men! Your world is like clouds, swiftly changing." Therefore, it

was no wonder that they looked to the sky in search for good pastures for their

camel herds and their own well-being. They did not think that one day, as their

Emir foresaw, they would be showered by plenty of good from underground, and not

the sky.

Return to Index

The people of the Arabian Gulf have undergone rapid and profound

transformations during their own lifetime, so much so that now they indeed talk

about old times as if they were only stories to be told. During the initial

phases of the black gold rush, from the early 60s to the late 70s, the camel and

its desert ecology were swiftly neglected and marginalized. It was not easy for

traditional socioeconomic organizations based on a subsistence economy to adjust

rapidly to an entirely new economic system linked to the complex and aggressive

capitalist commercial forces of the global economy. This resulted in the

collapse of the traditional economic activities like pearling, sea-borne trade,

fishing, ship building, small-scale oasis agriculture, and pastoralism.

The old small towns and villages dotting the shores of the Gulf were

transformed into glittering cities built out of concrete, steel, and glass.

These expanding capital cities drew like powerful magnets the Bedu, who were

always ready to move where the grass was greener. Now the Bedu of the Arabian

Gulf have settled in these towns and cities to enjoy the lulling comforts of an

affluent sedentary consumer life, with extensive free welfare services and

provisions.

Within the new economic context many of the previous benefits and uses of the

camel that were essential to the Bedu pastoral way of life came to disappear

quite rapidly. In the new oil cultural ecology the camel that once was the

all-wonderful, all-purpose 4-khuf (hoot) driving machine gave way to the

Toyota 4-wheel driving machine. The fast shift from camel to truck, as Chatty

(1986) succinctly described change for the Bedu, is seen on a large scale in

contemporary Gulf societies. The camel that once was known among the Arabs as safinat

al sahra (ship of the desert) has retired from sailing across the desert

sand dunes, and now gets carried on wheels. It is a frequent sight on the

highways of Arabia to see trucks of all sizes carrying camels to various

destinations including the camel racetracks.1

An ethnographic gaze while traveling along the highway between cities in the

Gulf can provide us with further pictures depicting the marginalization of the

camel. Many of the modern highways in a country like the United Arab Emirates

(UAE) are nowadays fenced with barbed wire for hundreds of miles so as to keep

wandering camels, as it were, off the fast lanes of modern economic life. During

the initial phase of building the highways across the wide desert terrain car

accidents caused by wandering camels were fatal and alarming in their frequency.

Thus came the need to fence the highways to keep camels off and provide road

safety, particularly at night for the new Gulf man as he moved about in his

air-conditioned vehicle in the modem traffic of his new oil ecology, where the

car and the mobile phone rule supreme as the new technology in Steward's sense

of the term. 2

Return to Index

The rapid marginalization of the camel experienced throughout the Gulf and

Arabia du6ng the early decades of the oil boom in the 1960s and 1970s came to be

halted in a significant way. The collapse of traditional economic activities

within the context of the overall rapid economic modernization triggered by oil

wealth brought a realization of the importance of preserving and reviving

traditional culture. The camel in general and racing camels in particular came

to be in the thick of this cultural revival phenomenon. Racing camels, known

locally as al hejin 3, are

returning in large numbers, carried by trucks from near and far throughout the

Gulf to the large- racetracks built nowadays near most major cities. As in the

UAE during the long racing season, from October to April, the slender tall hejin

become the center of attention for increasing numbers of local and foreign

enthusiasts and onlookers.4

While they perform on the track, the television screen brings this sport to

every family in the comfort of their own homes. Moreover, they bring all the

people involved in this growing industry not only cultural satisfaction and

social honor but actually large material benefits. These racing camels bring

their owners and trainers luxury four-wheelers and beautiful sedan cars such as

Mercedes and BMWs.

In anthropological/sociological research we often look into the timing of a

given phenomenon and its scale. Why is a specific phenomenon appearing at this

particular time, and why is it manifesting itself in certain magnitudes and

intensities? Over the last two decades the sport has grown at an exponential

rate: for example, 4,000 camels took part in the eight day finals of the 1996/97

camel racing season at Nad Al Shiba track in Dubai, performing in 154 rounds. A

similar number appeared on Al Wathba track in Abu Dhabi Emirate immediately

following the Dubai races.

In view of the fact that cultural revival is growing so fast as to reach

levels of national industry in the Arabian Gulf societies, the aim of my

research is to document this process as it is manifested in camel racing. In

addition to ethnographic documentation of the phenomenon in the United Arab

Emirates, other aims can be stated by a number of analytical questions that

direct our attention to explore the various dimensions surrounding the return of

the camel as a heritage revival phenomenon in the Gulf. Why is heritage revival

appearing at this time juncture as an expanding national cultural industry? How

is this cultural production being affected by rapid modernization processes that

are heavily influenced by larger globalization forces? What are the continuing

and changing aspects and elements in the reproduction of such cultural

activities? Why and how are the state and other sectors of UAE society

supporting the preservation of national heritage? What are the multifaceted

dimensions and functions of this rising heritage phenomenon in the oil rich Gulf

societies? Why is the production of the past, of cultural nostalgia,

particularly significant in the context of what Davis (1991) terms

"statecraft and state formation" in present-day Gulf societies? How is

the oil state using its wealth to develop an appropriate political discourse to

preserve national identity, strengthen its own legitimacy, and solidify its

authority structure? It is hoped that: this research topic can illuminate

further the dynamics of cultural change occurring now in the Arabian Gulf.

Providing a meaningful analytical answer to the question of why camel racing

in the UAE and the Gulf is now being practiced on a large scale requires that we

go beyond the races and heritage revival as such, and contextualize them within

the broader ongoing processes of oil economy, the building of a modem

nation-state, and increasing global forces acting on the local culture. Here we

need analytical insights gained from combining both political economy and global

cultural economy perspectives. The first can inform us about the complex

interplay between leadership, politics, culture, domination, and economic forces

or conditions. The second perspective, which has been developed recently by

globalization theorists (Appadurai 1990; Featherstone 1990; Robertson 1995) will

turn our analytical attention to the interplay, fusion and/or reactions

generated between global and local cultural dynamics as the UAE society is

undergoing rapid change.

Return to Index

In the UAE, as well as other Gulf societies, heritage revival including camel

racing is reaching levels of national industry. This has involved the

mobilization of labor, capital, and integrated organization of many people,

agencies, and institutions. However, to give our ethnographic description of

camel heritage revival a historical framework, it is useful to present first a

brief sketch of camel racing in the past. This will enable us to contextualize

and appreciate the scope and complexity of the modem development of the races.

In the former pastoral way of life, the Bedu of Arabia utilized the camel in

maximal ways, not only to survive in the harsh environment in terms of food and

transport but also in raiding and numerous political activities as well as in

sport and recreation. For the Bedu it was an all-purpose 4-hoof driving machine

that was adapted and utilized in both material and symbolic cultural terrains.

Local informants explained that camel racing in the past could be viewed as

falling into two categories: races during "social celebrations" and

"competition races." In the old days such sportive recreational

activities were fully integrated within the mainstream of social economic life

of the Bedu which in general lacked the institutions of certain cultural

activities whereby numerous and elaborate rules get invented and established.

Races, which were performed on festive social occasions and celebrated by the

local community, included religious feasts, celebrating rainfall, weddings,

circumcision, and perhaps the occasional visit of a prominent tribal shaikh.

During such festive occasions people displayed their colorful rugs and cloths on

tent ropes. These races were basically an ardha, a show, which ran across

300-500 m. One or two men sang loud heroic war songs, and riders exhibited their

riding skills while brandishing their swords or old rifles, or stood holding

hands while two or three camels ran parallel to each other. When tribesmen

visited the villages or camps of their kinsmen during religious Eids, feasts,

they usually performed a short ardha race on their mounts before coming

in the tent to greet the people and share coffee and dates with them. In the

races of festive celebrations there were occasional individual competitions for

sport, but the winners received no prizes. Sometimes, however, in wedding

celebrations the first, or occasionally the first three winning camels got

prizes from the family of the groom. Prizes in those days were small symbolic

statements, basically shara (sign) or namous (recognition),

represented materially in a dagger, head cloth, or other items of clothing.

In competition races riders were usually arranged for the race a day ahead of

time, and the evening before the race they agreed on the starting point. A shara

(prize) was usually declared ahead of time. Such competitions were usually

arranged as a resu1t of a challenge (wahna) among camel owners, or it could have

been triggered by a visit of a leading shaikh who put forward a prize for the

race. Sometimes competing riders went and spent the night at the starting point.

Each would guard his mount carefully throughout the night to prevent foul play

from other competitors. The race usually started early in the morning. Racing

distances were relatively short, extending between 3 to 4 km. Unlike today,

camels sat down at the starting line, and upon hearing a short cry, they rose up

and ran. The owner of a particularly fast camel was usually asked not to

participate. Instead he was given a sadda (compensation) in order to give a

reasonable chance to other competing camels and to make the race more

unpredictable and exciting. Rules governing age categories of competing camels

and the ages and weights of riders were almost nonexistent. As recently as the

early 1970s, race camels were ridden by their owners, usually the nimble

youngsters in the family.

The advent of oil in the emirates in the early 60s did not bring about an

immediate change to camel racing. There were local races in each emirate, and

these usually preceded the larger inter-emirate races. In the Dubai local races,

for example, they sometimes ran the long distance of 15 km a1ong the beach from

Chicago Beach to Al Shindaga, or a lesser distance from Al Safa to Al Shindaga.

Usually shaikhs gave prizes to winning participants. Races in the 60s and 70s

took place in a seih, rain flood flat land as in Seih Al She'aib in Dubai, upon

which later the Dubai-Abu Dhabi highway was built. The starting point for this

race was known as al medfa' and the finishing point as al mehjel.

As noted by one informant, challenge and passion were the high excitement of

the locals, particularly in the inter-emirates races. These larger races were

always headed and patronized by the ruling shaikhly families, and the prizes

were provided by the ruling shaikh of the emirate in which the race took place.

Even in these races, rules regarding camel types, age categories or riders were

lacking. Old films of the emirates in the late 60s show footage of camel racing

where large numbers of cars follow the camels, creating dust storms and adding

to the feeling of general commotion and excitement.

The production and organization of modem camel racing in the UAE is radically

different from 30 years ago. Then the races were held occasionally in small

local communities; now the scope and depth of change has touched all aspects of

the races, so much so that they now appear beyond recognition for many old

locals. These modem developments can be delineated by an analytical description

of the different aspects which make up this still expanding heritage sport. It

should be noted that these various aspects, functions, and dynamics are all

interconnected in complex ways; they are identified here separately only for

analytical purposes.. They include the modem media, new organizational

developments, economic, political, and cultural aspects as well as aspects

related to the interplay between local and global forces.

Return to Index

Modem mass media, represented by television, radio, newspapers, and magazines

is the leading agency involved in the production and propagation of heritage

revival activities in contemporary UAE society. With the broad transformation of

society came an increasing decline of traditional methods of communication.

Subsequently, television has emerged over the last 20 years to rule supreme over

all other agencies of modem communication technologies. Every year during the

long camel-racing season (October to early April), television has made the

spectacle of camel racing, as well as other types of heritage festivals, within

reach of every home.

Those who get attracted by camel races on television and venture out to the

track to see performances in reality are caught in an ironical situation.

Spectators find themselves in front of television screens at the racetrack

itself, as this is the only way to watch the slender, racing hejin run around

the very large track. The track is locally referred to as al doura

(circle) or al mirkadh (running place), and since it is 10 km in

distance, the only part of the race, which can be seen from the stadium, is the

start and finish, about 3 minutes in total. The remaining 15 minutes of the race

can only be viewed on one of the long line of TV screens placed especially in

front of the 100m stadium, accompanied by the commentator's voice thundering on

the air.

Marshall Macluhan' s famous statement, "the medium is the message"

(1964: 23), is very applicable to the growing phenomenon of camel racing in the

Gulf. Television as the ultimate modern communication technology has indeed

played a significant role in the evolution and popularization of this cultural

sport. It has not only fashioned the nature and style of producing cultural

messages related to camel racing, but has also shaped other supporting

activities surrounding this sport.

Wide access to television has empowered people to "compress space and

time" (Harvey 1989: 271) watching world events in ease and comfort. Unlike

writing, televised messages are direct; they carry a sense of immediacy and

"restore presence" of the events transmitted, and in this lies their

great appeal. Cultural messages transmitted by television do not require

elements of mediation specialized training leading to literacy between the

producers and receivers (Williams 1983: 111). Because of this, television has

enabled state agencies and other organizations involved in the production of

camel heritage to overcome certain constraints usually associated with

illiteracy. As most of those involved in the breeding and/or training of racing

camels in the Arabian Gulf are still illiterate or barely literate, television

production has an important effect.

On one of my visits to the encampment at the Al Wathba racetrack in the Abu

Dhabi Emirate, I asked a Saudi to come and watch the races with me. He replied,

"Why bother? It is all here in front of me. It is direct on the air. You

can even get a better commentary here on television." He was one of the

fortunate few to have pitched his tent close to the electricity mains supply,

and as a result he had furnished his tent with modern conveniences: TV,

refrigerator, and a fan. His statement reflects a common attitude among those

involved in camel racing; indeed, it explains the absence of large crowds at the

camel racing stadiums although the sport is tremendously popular, especially

among the Bedu.

To facilitate this televised sport, a special road has been built alongside

the racing track for the mobile television cameras, so that the entire race can

be viewed. Various modern television techniques are also utilized to make such

heritage races more attractive to make such heritage races more attractive to

watch. For example, often the TV screen is split: one half displays the

panoramic view of the race, the other shows the leading camels in close-up. In

addition, the finale of the race is viewed from a height as well as the side.

Television documentaries and other event-related programs on cultural

heritage, including camel racing, produce complex messages of multiple meanings

and functions. They can be viewed as both instruments of state political

legitimization and domination, and equally important, as means through which

local cultural identity is revived. The cultural discourse used in these

television heritage productions employs multiple forms, strategies, and styles

in order to drive home to viewers numerous simultaneous messages. During the

final camel races in April 1996 in Al Wathba in the Abu Dhabi Emirate, the

commentator of a special program on the races expounded at length on the place

and importance of camels and camel racing in present-day UAE society:

Shade, water, palm trees, and the camel are vocabularies which when joined

together mean the life of the true Arab Bedu. They also mean heritage filled

with glories. They mean noble deeds, high morals and fine qualities all of which

have become features of the Arab man. They make up his identity, where our

ancestors lived a life of desert hardship and scarcities. It was then inevitable

that they migrated in search of these essentials for their own life and that of

their animals. "Look for your friend before you look for your road" is

a saying whose meaning is clearly expressed when we come to the camel, the best

of friends.

The huge expanse of desert in the Arabian peninsula and other Arab lands

imposed upon the Bedu specific harsh modes of life that required endurance,

patience, and determination. In spite of life hardships, being faithful to one's

homeland was the ultimate noble motive that led the Arabs to build their lives

in the desert. In such life context the value of camels grew in the Arab's life

to become equal to his honor, glory, and dignity. These are attributes of honor

that the Arab is ready to pay for with his own life for their preservation.

Camels were not only used for migrating across desert land; they provided a

source of livelihood with their milk, wool, and meat. Most importantly, camels

occupied a large domain in the history of Arab glories. Day after day the bond

between the Arab man and his camel becomes stronger, and the camel's place and

significance increases. Isn't the significance of the camel stated clearly in

Allah's Great' Book, and in the Sunna of His Prophet as a testimony of the

Creator's great miracles in His own creation? Also the camel is to be seen as

concrete evidence of Allah's powers and his wonders in creation; and a

motivation for men to reflect about Allah and His ultimate knowledge.

With the passage of time the camel was transformed from being only an

instrument of transport and migration to an important pillar, a significant

feature in our heritage and traditional Arab character. In historical,

religious, and civilizational terms, camels can be associated in a long chain of

pride and glories. Built on this belief and in appreciation for the precious

heritage of the past His Highness Shaikh Zayed Bin Sultan Al Nahyan, President

of the State, has formulated his goals and directives emphasizing the necessity

for showing appreciation and respect for this heritage, and to encourage our

nationals to practice the sport sibaqat al hejin (camel racing). Under

the rulership of His Highness, President of the State, may Allah protect him,

and due to his support of heritage, the value of al hejin is increasing

steadily.

This type of media information is significant as it simultaneously

encapsulates multiple knowledge discourses. It explains the adaptational bond

between the Bedu and their camels. More significantly, it invokes heritage

sentiments, cultural historical nostalgia, and other political and national

ideological messages.

Return to Index

Changes in the organizational aspects of the production of the races are the

most evident and notable. They are heavily affected by the adoption of

technological innovations and methods of television media information.

The systematic modem development of camel racing in the UAE started in the

early 1980s. Those who were involved in the development of this sport throughout

the Gulf found themselves in a difficult situation, as this was a new sport and

there were few prior experiences on which they could draw. However, some

organizational methods and rules in horse racing have been adopted or modified

to suit camel races. For example, races are classified according to categories

of breed, age, and distance. In their quest to develop camel racing and promote

its popularity at home and beyond, people involved in this young-old sport had,

as informants pointed out, to learn the hard way; learn by trial and error. They

had to invent, adopt, and reassess their progress year after year. The

accumulation of the last fifteen years of experience has led to the development

of the sport according to an elaborate set of policies and rules that have now

brought greater order, fairness, and standardization to this cultural heritage

enterprise.

The realization of such a quest has been made possible, as the media

frequently reminds one, "by the inspiration, guidance, and instructions of

Shaikh Zayed, the President of the UAE, and his brothers, their excellencies,

the members of the Supreme Federal Council, Rulers of the Emirates." In

this context emerged the need to establish the Camel Racing Association (CRA) in

the UAE on 25th October 1992. The goals of this association are to continue the

development of this heritage sport by giving it institutionalized forms

throughout the country, made up of seven emirates. Basically this has meant

bringing standardization and uniformity in the organization and other aspects of

racing.

Return to Index

The building of modem racetracks (referred to by the locals as al markadh',

lit. "running place"), is one of the most obvious developments of

camel racing in the UAE. As noted earlier, these racetracks have stadiums

ranging in their size and beauty , depending on the cities they neighbor. Most

of them were built in the early 1980s. The most famous ones are Al Wathba, about

30 km southeast of Abu Dhabi City, Nad Al Shiba, 10 km south of Dubai, and Al

Ain track in Al Maqam, 20 km west of the oasis city of Al Ain in the interior of

the country. The lesser tracks include Al Samba and Al Madam in Sharjah Emirate,

Al Siwan in Ras Al Khaimah, and Al Labsah in Umm Al Quwain. In addition, small

racetracks are built in desert areas where large concentrations of Bedu involved

in camel breeding live. These tracks, found particularly in Abu Dhabi and Dubai

Emirates, are used for training and local races, where buying and selling of the

hejin take place.

The major tracks, like Al Wathba and Nad Al Shiba, are well constructed with

attention to heritage-oriented aesthetical features. For example, Nad Al Shiba,

built by the Dubai local government, is an integrated camel racing facility of

the first order, stretching over 25 km2. It contains two tracks; the larger one,

known locally as al doura al kabiera (the large circle), is of 10 km but

can be shortened with specific openings and enclosures to 8 km. The smaller

track is located inside the larger track, and again through the use of openings

and enclosures it can accommodate races of 4, 5, or 6 km for younger camels.

The stadium, which faces the finishing line, is built in the shape of a large

white tent perched on a green bill of immaculately tidy lush green lawns,

swaying palm trees and flowering shrubs.

Eight flapping UAE flags on the spine on the tent give the whole structure a

feel of poised beauty in flight. In functional terms the tracks are provided

with all necessary services, personnel and equipment required for the six-month

racing season. The stadium has a seating capacity of 1,000 with a VIP section in

the centre. For the management of the races, the track is provided with a tower

for TV cameras at the finishing line, a special tarmac track for two TV cars, an

ambulance, and several microbuses which carry specialized personnel involved in

the management of racing in each round (shoudh). The stadium is provided

with TV sets in front of the seats, and sound amplifiers. Close to the starting

line there is a large enclosure to keep camels waiting for the races. Adjacent

to the tracks there is a police station, kitchen, toilets, a camel market of 56

shops specializing in food and accessories for camels, a mosque, a veterinary

centre, medical and drug testing clinic, and a large area of one square mile

primarily for the encampment of guest participants from neighboring Gulf

countries during the final months of the races. There is also a special area for

the display of about 150 luxury cars to be given as prizes at the end of the

season, late March or early April. More than 50 men are employed to maintain the

tracks and enclosures throughout the year. The CRA, Dubai Branch, hires them

from a company called EO (Engineering Office), and in their gray uniforms the

men, mainly from India and Pakistan, drive water trucks to sprinkle the tracks,

drive tractors to harrow and level the sand, and act as gardeners, cleaners, and

maintenance workers.

Return to Index

It is relevant to note that the lean, slim, and agile racing camels (al hejin) now seen on the racetracks are not a recent product, as the Bedu of

Arabia have always bred fast camels. Given their desert pastoralist mode of life

they did not need to possess many camels for transport as beasts of burden.

Their main concern was breeding large numbers of fast riding camels that they

used as mataya (mounts) in raiding and defense. This is in contrast to camel

breeders in the Sudan, Egypt, Pakistan, and Afghanistan who needed heavily built

camels primarily for transport and agricultural work.

The organizational innovation of introducing separate races for different

breeds of camel has contributed greatly to the development of the races, as the

specific categories of camel breed possess different physical qualities that

affect their performance on the track. Racing camels have been divided into

three categories, according to their physical type: a) the local breed, known as

al mahaliyat (local ones) or ra'iyat al dar (mistresses of

homeland), usually brown in colour, b) the Sudanese camels (al Sudaniyat),

which are usually a little bigger, faster, and white in colour, and c) the

interbreed (al muhajanat) of the first two.

Interbreeding has resulted, though, in the emerging problem of camel

identification, and to ensure fairness in the races paternity testing is now

carried out at the camel laboratory centre in Dubai. A laboratory analysis is

made of the father's and the child's blood, and if the father is a Sudanese

camel, then the child is also categorized as al Sudaniyat. Interbreed

camels are identified by a metal tag inserted under the skin on the neck, and

immediately before the races the camels are checked to confirm their muhajana

(interbreed) identity. Since 1997 the Sudaniyat camels have not been

allowed to participate in the races, and the intention is to ban this category

of camels altogether, and confine racing to the local, interbreed, and

occasionally Omaniyat (Omani camels).

Return to Index

Camel races are now organized according to sex and age categories, as well as

the different breeds. One of the responsibilities of the Camel Racing

Association, through a special lijna (committee), is to ensure that only the

appropriate camels run in each race category. Members of this committee are

experienced camel breeders who usually rely on teeth extraction to determine the

age of the camel. This move has introduced greater fairness to the races.

Table: Camel Categories

| Arabic Local Names |

Age in Years |

Distance in km |

Average Running Time (min/sec ) |

| Haq |

2-3 |

4 |

6.50 |

| Leqai/Madrab |

3-4 |

5 |

8.50 |

| Yetha' (male and female) |

4-5 |

7

8 |

13.00

14.30 |

Thanaya

Thanaya abkar (females)

Thanaya je'dan (males) |

5-6 |

8

8 |

14.00

14.20 |

Hool

Thulel (females)

Zumool (males) |

over 6 |

10

10 |

17.00

17.30 |

The table of camel categories shows the Arabic local names of the various

categories of camels divided by sex and age, the distance specified for the

races, and average running time.

Camels can continue racing until they are 12 to 14 years of age; then they

retire to the breeding farms. It is of relevance to note that just over 90% of

the racing camels are female. Usually only one in every 10 races is for male

camels; often the second round of the races is given to males. The male races

are further subdivided into two categories: khasaya (castrated) and ghair

khasaya (uncastrated); the latter represents the majority of races. There

are several reasons why al thulel (female camels) are dominant in the

races; first, most young male camels are slaughtered by the Bedu for social

celebrations, such as weddings. Only a few of the male camels are spared,

primarily for reproductive purposes. Secondly, female camels are usually faster;

by an average of 30 seconds in the race, and thirdly, the females are more

gentle and easier to handle. The races usually take place during the winter,

which coincides with the rutting season for camels. This makes the uncastrated

males quite temperamental and more difficult to control during training and at

the races.

Return to Index

Races are also organized according to the social categories of owners, a

strategy aimed at providing greater diversity and opportunities for competing

camels. Since racing camels owned by the ruling shaikhs in the various emirates

are of the best stock, they have high chances of winning every event that would

be devastating to the ordinary Bedu breeders. Thus there are three types of ash

wadh (rounds): a) races specified for al shuyoukh (shaikhs); b) races

for al shuyoukh and al qaba'il (tribes), also known as a'am

(general races); and c) races specified for 'abna' al qaba'il (sons of

the tribes), also referred to as lil jama'a (the tribal groups).

Usually hejin al shuyoukh are run in the morning (7:30-10:00 a.m.),

and races start early so as to make maximum use of the fresh hours of the day.

Most of the races specified for the Bedu take place in the afternoon (2:30-5:00

p.m.). These races are often watched by the camel breeders for the shaikhs, who

come to identify particularly good racing camels, and may purchase them for the

shaikhs' camel farms.

Return to Index

For the last twelve years strict feeding programs have been introduced for

the overall welfare and "running fair" of the racing camels.

Nutritionists have been employed from the Netherlands, and a feedmill has been

in operation for many years with a British manager. All feed except alflafa

(locally called al jat or barseem) is imported, and mixed in the

feedmill. According to specialists at the Dubai Veterinary Laboratory, racing

camels nowadays have a well-balanced diet, a high-energy feed consisting of oats

and barley, with vitamin supplements and trace elements added to the feed. While

camels are not true ruminants, they do nonetheless ruminate and need a lot of

fiber. During the racing season, camels are put on a special feed and are not

allowed to roam and forage in the desert.

On the other hand, breeding camels are allowed to feed in the desert, with

additional special feed. Usually a baby camel is taken away from its mother when

it is between 13 to 16 months old, and is then put on a race-training program.

This will produce a fast camel at the age of 3 years, when it is allowed to

enter the races. The mother can give birth to another calf after about 13

months.

The steady advances in camel health care are reflected by the growth of the

Central Veterinary Research Laboratory in Dubai, which was established in 1986

primarily for the purpose of experimental research into reproduction of better

breeds of racing camels, control of camel diseases, and to ensure the general

welfare of the animals. The centre started with 3 employees, but by 1997 it had

grown to 25 specialists, including 5 biochemists and 20 scientific assistants.

Various other institutions are associated with the laboratory, including clinics

for camels, horses, and falcons, and reproduction and fertility laboratories.

The ruling family of Dubai alone employ 10 veterinarians recruited from Pakistan

in their special camel clinics, and these bring camel disease cases and

specimens to the laboratory.

According to Dr. Ulrich Wernery, a German microbiologist who joined the

center as its director in 1987, the work of the center has helped in eradicating

and controlling many camel diseases. Consequently the health of camels has

improved steadily, not only in the UAE but in Somalia, Sudan, and Pakistan, and

currently the center is proposing the establishment of a veterinary school in

the UAE. The center examines every year 15,000 camels owned by the Dubai shaikhs

and, to a lesser extent, the Bedu camel breeders. Every camel has a health check

once a year, some more frequently. The purpose of this is to chart the running

performance, and especially the relative ratio of red blood corpuscles in the

blood. One of the main objectives of the center is to help in the production of

faster racing camels, and over the last three years the average winning time of

a 10 km race has been reduced by two minutes.

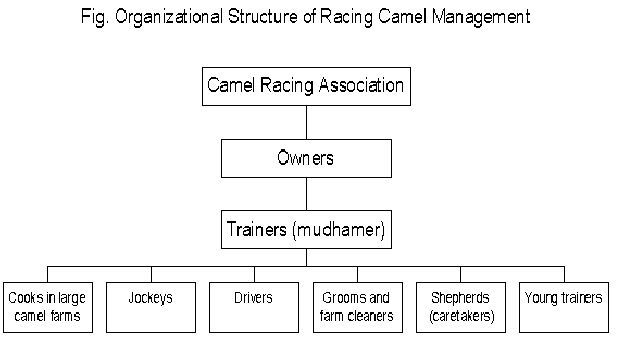

The production of faster racing camels is not confined to producing good

genes and maintaining high quality health care for these lean beasts of the

desert. Equally important is their training for the track, their feeding, and

other aspects of their management. An elaborate organizational hierarchy has

emerged over the last two decades, reflecting the new dynamics generated by oil

wealth and the interplay of local and global forces and methods in camel care

and training. At the top of the hierarchy reside the owners of the camels,

notably the ruling shaikhs of the various emirates. They own the finest and

largest number of racing camels, and as the media states, it is their vision,

financial support, love, and attachment to camels, policies, guidance, and

inspiration to develop the races that have given rise to the establishment of

the CRA in the UAE and the phenomenon of heritage revival at large.

In hierarchical terms, next to the shaikhly owners there are a small number

of wealthy merchant families who own camels, particularly in the Emirates of Abu

Dhabi, Dubai, and Sharjah. Their interest in racing camels is motivated by three

main reasons: for commercial purposes, in terms of buying and selling camels;

the attainment of prestige; and emulating the ruling families in heritage

revival. Thus they come to share in social honor and the symbolic capital that

is manufactured through the modem media. The Bedu tribesmen's position as owners

of racing camels came about because of the collapse of traditional camel herding

and camel transport economy, and their capacity to shift their traditional

knowledge and skills to the breeding of racing camels in the context of the new

oil economy. Many of these owners possess only a few camels, and equally

important, they rely on the generosity of the shaikhs to employ them as trainers

of the shaikhs' camels. Further notes on ownership will be raised in more detail

under the economico-political aspects of racing.

The CRA as a managerial body is involved in all aspects of camel racing

throughout the season; the larger umbrella organization embodies smaller

branches in each of the emirates. It also mobilizes various committees whose

supervision is essential for well-controlled, orderly, and fair races that are

also colorful, exciting, and enjoyable to watch.

The Association's duties go beyond formulating rules necessary for greater

development of the races, and include a) preparing the racetracks and ensuring

they are well-equipped; b) ensuring equal training and participation

opportunities for all camel owners (all interested citizens have a right to

participate); c) making a detailed schedule for the hundreds of races each

season, culminating in the finals in Dubai and Abu Dhabi with the winners

presented with prestigious trophies donated by the leading shaikhs; d) selection

of referees and judges for the races; e) contacting commercial and other

establishments for donations of attractive prizes (4-wheel drive luxury

vehicles, BMWs, etc.); and f) ensuring wide press coverage of racing events.

At the races themselves numerous lijan (committees) can be seen at

work. There is, for example, a committee to identify and control specific camel

age and breed categories, which issue identification markers for the races.

There is also lijnat al ta'rief, the committee to identify the owners of

running camels, who accompany the TV commentator round the racetrack to give

information on the leading camels. Their work is made easier nowadays as the

larger camel stables have adopted specific colors for the vest of the rakbi

(jockey). This strategy has been generalized across the Gulf Arab countries, as

racing camels from different countries participate in many of the large races,

which are timed to allow racing enthusiasts to truck camels and trainers from

one country to the next (mainly UAE, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Oman).

There are also lijan to watch the start and finish lines. The finishing line

committee is responsible for identifying the first ten racing camels for each

race, and can resort to televised images in cases of dispute. The winners

receive a card that is immediately taken to a mobile office, set up in a car,

where a paper is signed and stamped. This is then taken to the "Prize

Awarding Committee," basically a treasurer and an accountant, who sit at

two small desks and distribute cash prizes varying in value according to the

race positions achieved. The owners of the first three camels, however, do not

receive prizes immediately. These camels are taken to a clinic to be tested for

the use of drugs, and the owners have to wait a day or two for the results. Any

use of energizing drugs will not only disqualify a camel, but entail loss of

face and personal integrity for the owner. At the larger races, however, the

first three camels do receive immediate honorary treatment; their heads are

decorated with saffron imported from Syria, and they are paraded in front of the

stadium for a few minutes, so that VIPs and others have a full view of their

stature against the background of manicured lush green lawns.

There is also a medical committee, consisting of paramedics who accompany the

racing camels in their ambulance. If any rakbi looks sick, as sometimes the boys

suffer from race nausea, then the ambulance staff will stop him and relieve him

and the camel from the exhaustion of the long race.

The ruling shaikh's gesture of hospitality to all those participating in the

races expresses itself through the work of the lijnat al dheyafa, the

hospitality committee. The staff are involved in distributing foodstuffs, as

gifts from the shaikh, to all the breeders, trainers, and caretakers of racing

camels, who usually camp with the camels in special designated areas near the

racetracks, or al race, as it has been arabized and frequently referred

to by the Bedu. These food gifts include lambs, sacks of rice, tea, sugar,

coffee, cardamom, cheese, condensed milk, etc. Participants coming from outside

the emirates are welcomed with added attention and generosity.

Return to Index

Racing camel trainers occupy an important position in the management

structure of camel racing outside the activities supervised and/or performed by

committees of the Camel Racing Association. As with breeding, training is still

the domain of the Bedu. The trainers are known locally as al mudhamer

(literally the person who makes the camel lean and fit), and come from desert

camel-based families where traditional knowledge and love for racing camels is

in the air around them. The mudhamer's personal success in training winning

camels is usually the road to his fame, as he then becomes well known and may be

approached by the shaikhs to train their camels. Since training plays an

important role in giving the camel greater opportunities for winning, good

trainers can achieve both fame and fortune in the racing camel world of oil rich

Arabia. Top trainers are a scarce commodity and can actually fetch high prices

for their expertise and skills.

There are two types of camel training. The first type is referred to locally

as al adab, which means proper behavior, or al ta'ah (obedience)

as the Sudanese trainers call it. This involves breaking in the young camel when

it is about 13-14 months old; the process takes about 1 to 3 months.

It involves attaching the young camel by rope to an old quiet well-seasoned

camel known as al qeliesa, to act as a guide and companion in the

training process. The young camel is trained to wear the al khidham, the

rope fixed around the head to control the camel's movements, and the al

shidad, the soft blanket saddle. It becomes accustomed to being mounted by a

young rider, and most importantly, it gets trained to run on the track. One of

the common sights on al mirkadh (the racing track) at non-racing times

are young, often teenage, Balochi, Sudanese, and Somali trainers riding their

qeliesa camels with their sticks in hand, each leading two to four young camels

that in turn have small rakbiya (plural of rakbi) perched on their backs. This

training is done frequently until the camel acquires the running aptitude so

that she can negotiate the al mirkadh with ease and confidence. When the

camel is three years old, she graduates to enter the al mirkadh as a

member of al liqaya (the three year old crop of racing camels).

It should be noted here that the qeliesa riders-cum-trainers were

often a few years back small rakbiya riding in the heat of serious races.

However, their fast body growth and increased weight have forced them to

graduate from the backs of the lean athletic camels to the relatively heavy and

quiet qeliesa, which themselves have been forced to retire from the

track-and-field athletic business. While sitting in Nad al Shiba camel stadium

in Dubai I turned to Sudanese boy who sat next to me. Guessing that he is

involved in the camel business, I asked him, "What do you do?" "I

am a trainer," he answered half shyly. Then he explained that only three

years ago he was a rakbi, but now he breaks in camels and helps in training them

on al mirkadh. His father and two uncles also work in the camel business.

Apparently over the last fifteen years the northern central region of Sudan (Um

Delaiq) has been exporting many camel experts, mostly from the camel tribes of al

Badaheen, al Kowahla, and al Hawara. Similarly the Rashayda

tribe in the Kasala region of Sudan has been sending camel boys of all ages to

the UAE as well as other oil rich Gulf states, particularly Saudi Arabia.

The second and more important type of training is called al tadhmeer,

which is aimed at achieving high athletic fitness for racing camels. The term al

tadhmeer literally means "making the camels slender and fit." The

trainers in charge of the process are locally known as al mudhamer, and

are mostly Bedu. There are those who got into the profession in a de facto

manner as they began breeding their own pure pedigrees of racing hejin, and

subsequently got involved in training them to enter races when the racing hejin

phenomenon started with force in the early 1980s. However, some Bedu trainers

were hired as mudhamers for the training of racing camels bought by the shaikhs.

There is, however, a strong link between the two, as often a shaikh upon buying

few camels from a Bedu breeder decides that the camels should stay with him as

their caretaker and trainer, as he is the best person to know and care for the

camels. Then through the shaikh's private office the mudhamer gets allocated the

required finances to establish an 'azba (camel farm). This means that he

gets a set monthly salary, wages for laborers, a four-wheel drive car, a mobile

phone, radio, water tank truck, petrol expenses, necessary fodder, and so on.

Most mudhamers I talked to repeated that they do it not only to gain an income

but also because they love to do it. They relate to it both as a job and a

hobby, and in this lies their dedication and total engagement to the hejin. In

fact, many of them have succeeded in attracting their adult sons who were doing

their university studies into this competitive brave new world of camels.

There is more or less a uniform camel training pattern followed by al

mudhamers. However, when talking to them they present themselves as training

experts who are different from others in some variation, strategy, or method.

The training program usually begins early in July for the weaker camels, while

stronger ones are put on the training regime around late August. The program

begins with al tasrieh, taking the camels out for walking in the desert

early in the morning. Initially the al tasrieh distance is around 20 km;

in the training context al tasrieh means to let camels roam and forage

while at the same time they are guided to do some serious walking. The camels

are brought back to the 'azba before the scorching midday heat. Upon their

return they get fed al jat (alfalfa) and barley and are given water. Then

they rest in al mersagh (the shaded shelter) until around 3 o'clock when

they are given water and a large handful of dates.

At the beginning of October the training and feeding change in several ways. Al

tasrieh (sometimes called al minshar) walking distance is increased

to 40 km a day. Food and water are carried out to the camels in al minshar

(the roaming pasture land). They return to al mersagh between 4 and 6 0'

clock in the afternoon for their dinner. The camel eats two qlala (large

bunches) of al jat daily. About two months before the races some of the

camels are selected by their trainer as having a good opportunity to perform

well, and these are given special feed that includes minerals, milk, and honey

in measured quantities. They also receive greater attention, not only in terms

of more frequent medical checkups but also in terms of their general welfare and

health care against insects, dirt, and changing weather elements. The al

tasrieh process usually consists of 3 to 5 hours purpose-oriented walking

daily, with the aim of making the camel lose fat, and become well trimmed and

fit.

Various workers are employed in the camel 'az ba under the supervision

of the Bedu mudhamer, and each is assigned specific tasks to perform daily. For

example, an 'azba with ten racing camels requires three to four workers.

One will be involved in taking the camels out for al tasrieh (walking and

foraging), while the second will be responsible for preparing fodder and water.

A third may be assigned the task of keeping the camels clean and groomed. In

addition, the rakbi boys usually will be seen around as helpers in miscellaneous

tasks. While they are actually hired as camel jockeys they also get general

training as caretakers of camels under the supervision of their father or male

relative. Sometimes a rakbi will work and live under the wing of a compassionate

mudhamer who more or less adopts the young boy and sees him grow up to become a

young camel trainer by the time he is 15 years old. Most of the hired laborers,

including tile young trainers, come from neighboring poor countries like Sudan,

Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Somalia, Mauritania, and also Oman. This

category of laborers represents the least paid and lowest stratum within the

hierarchical pecking order of this camel cultural industry. Their monthly wage

averages around DR. 600-800 (U.S.$180-220).

In addition to the regular and systematic al tasrieh, which is aimed

at giving the camel general leanness and fitness, comes running training called al

tajheem, which usually begins in early November. While some al tajheem

exercises are done on small local rings, the serious training is conducted on

the major racetracks. The long period of preliminary races, extending from

October to the end of January, is arranged in such a way that they take place

alternatively every second week. This allows camel owners and trainers to bring

their camel athletes to exercise on the track. At the end of morning and

afternoon racing sessions hundreds of camels can be seen entering al doura,

the ring, for al tajheem practice. The process is controlled in that only

five to ten camels are allowed to start at a given time to avoid overcrowding

and injuries.

The distance is not fixed but decided upon by the trainer, according to the

distance the camel is expected to run in actual races and the trainer's own

plans and training program.

The goal of al tajheem is to get the camel used to running over

specified distances. During the al tajheem period the quality of the camel's

diet improves radically. Most trainers offer their fine athletes additional rich

nourishing foods like dates, barley, cow's and goat's milk which is mixed with

very expensive natural local honey ($150-200 per kilo), purified butter and

local thick pancakes (al qures). Intake of such rich food compensates for the

tremendous energy lost during al tajheem training.

Racing camels also undergo a further training process called al tahfeez,

literally meaning "to prod the camel to empty her bowels." This

usually takes place two days before the race. The camels are then covered with

specially tailored blankets, and led away to the camp where they are washed.

They get a little water and alight meal, are covered again, and then their

mouths are covered with a special hood to prevent them from eating further. The

following day they spend in total rest and fasting in preparation for their

participation in the races.

It is worth noting here that good mudhamers become famous throughout

the land primarily because of televised media, as their names are always being

mentioned by TV commentators during the big races. In fact, the camel rakbi'

s uniform, in addition to the colors of the owner, now carries a special stripe

of a particular colour to identify a specific mudhamer, since each of the

shaikhs employs dozens of mudhamers

One Sudanese man in his early twenties from the al Rashayda tribe told

me the story of how' he and his older brother were recruited along with many

others as camel rakbiya in 1982:

My brother and I were in primary school, he was in the fifth year while I

was in the second year. We were taken from our village and spent about 15 days

in Khartoum. We were about 15 boys, and when we arrived at Abu Dhabi airport we

were taken away in small vans to Zayed City in the desert, west of Abu Dhabi

City. The men in charge of me sent me to school for one year. The beginning of

my experience as a camel rider was difficult and very tiring. Sometimes I felt

sick and I used to stop the camel. However, I soon learnt the skills of camel

riding and became quite good at it. My brother was then taken somewhere else, to

another camel 'alba. For a while I didn't know exactly where he was. After four

years I quit my 'alba and ran back to the 'azba where I was initially and

officially assigned. I moved to work in different camel farms and finally came

to see some of our relatives in the Al Ain region. Then we were both fortunate

to get hired by camel people in Al Ain. Now I have gained experience and

intuition about camels over the last 16 years, and most camels I nominate as

winners usually win.

The two brothers and some of their Rashayda relatives are now involved with

other Sudanese camel people in free-lance trading in camels. I was informed by

many Sudanese informants that the monthly salaries of the rakbiya used to be far

better than the current low salaries. Rakbi used to earn between 1200-1300 DH,

but now for Arab boys the monthly wages are 800 DH. The recruitment of many

rakbiya from Bangladesh, Somalia, and Pakistan have led to the lowering of wages

earned by such young gallant riders to 500-800 DH per month (around $150-200).

In addition to the material and moral support of the ruling shaikhs, the

rapid evolution of camel racing in the UAE is in part due to the continuing work

and dedication of the CRA. I will note here only a few of the rules and

regulations set up recently by the CRA to indicate both the wide scope and

coverage of small details which have in their totality advanced an evolving

cultural sport. As noted earlier, the CRA' s rules cover a wide range of

organizational aspects of the races. There are rules specifying racing dates,

camel categories, and distances. For example, rules written in 1993 state that

camel races shall start in all racing tracks in the UAE from the first of

September every year. The rules then specify the names of camel categories and

distances throughout the season, which usually ends in late March or early

April. "Races shall be run once or twice every month on Thursdays and

Fridays in accordance with the program set for this purpose. Other races may be

run on national or special occasions or during official festivals. Two or more

special races with large cash prizes shall be run annually; such races shall be

held during the racing season and under the supervision of the Camel Racing

Association. These races shall be called the Zayed Grand Cash Prize Races, and

dates, value of cash prizes, and programs of these races shall be determined in

due course."

The rules state that the number of camels participating in each round of the

race shall be between 25 and 30 camels. "Camels which their owners wish to

participate in the races shall be registered in order to distribute them

according to the number of rounds. Registration shall be made serially and on

'first come first served' basis four days in advance of the fixed date for the

race." On young camels it states, "Young camels under the age of al

yetha' shall be prohibited from participating in the races." On the

Sudaniyat category of camels it states that "Two rounds only in each race

shall be allocated to the Sudaniyat camels. One round for the shaikhs, combining

hoof and zumool, and one round to tribesmen." With regard to camels given

by the shaikhs to tribesmen it is noted "a) Camels given as a gift from

their excellencies the shaikhs to tribesmen shall be identified and b) such

camels shall be named, registered, photographed, and branded for identification

as the property of (x) person."

The CRA also made regulations in 1993 on the camel jockeys: "a) small

children are not allowed as camel jockeys; b) the jockey's weight should be

similar to the international standards of the horse jockeys and their weight

shall not be less than 45 kg; c) the jockey shall be medically examined to

ensure his fitness; d) the jockey has to wear the protection helmet; e) each

jockey shall be given an identity card which is issued in accordance with the

conditions acceptable and approved in all emirates and racetracks; f) persons

who breach these specific regulations set in respect of the jockey as indicated

above will not be allowed to participate in the races of the season."5

On dharb al hejin (camel beating) the rules clarify "a) beating

camels is not allowed at the start of the race until the distance of 1.5 km is

reached; b) in accordance with principles of animal welfare, beating racing

camels should be light and directed to alert and to prod the camel for greater

speed; c) branding the jockey's stick around is not allowed as this may cause

injury to others on the track."

In a similar fashion one finds numerous detailed rules on the number and

identities of cars running inside the ring parallel to the racing camels, rules

on control or prevention of certain camel types which disturb the smooth running

of the races and even rules on the order and proper quiet behavior of spectators

in the stadium.

It should be noted, however, that some of these rules are subject to

modification. For example, the Sudaniyat camels and their like, called al

harayer, have been banned since the 1997 season from participating in the

races. In accordance with the directives of His Highness the President of the

UAE, Shaikh Zayed, a new rule was formulated in May 1996 separating racing

camels into two categories: al muhajanat (interbreed) and al mahaliyat

(the local thoroughbreds). This is aimed at giving the local purebred camels a

greater chance of winning as the types and thus the number of competitive camels

are narrowed down. The rules have also been changed with regard to the jockey's

weight. Although the CRA formulated a rule in January 1993 that his weight

should not be less than 45 kg, only six months later it was voiced by the Bedu

involved in the races that this rule was not realistically suitable. As a

result, the CRA' s regulation on the issue of jockey's weight was changed to

"not less than 35 kg." One can see small boys perched like birds on

the top of these slender camels.

It was argued by the camel experts that the lightweight jockey is very

important in camel racing. This is not only to achieve greater speed, but it

also relates to the fact that camels do not mature before six years. This is why

the 10 km races are confined to camels that are six years old and more.

Repeatedly putting a heavier adult jockey on young racing camels may damage the

camel's spine. Unlike the horse, it is not possible to put stirrups on the

camel's back so that the jockey can stand and thus distribute his weight on the

whole body frame of the camel.

Additional organizational details and rules are added every year during the

final races. In the program booklet distributed at the Dubai camel racing finals

in February 1998, there are. the following notes on the first page from the

organization committee: "The organization committee will give medical tests

(check on the use of drugs) to the camels winning the first three positions. We

request the co-operation from every one. The Sudaniyat camels are strictly not

allowed to participate with the local breed camels. Warning: it has been noted

lately that some camel owners and mudhamers are providing their jockeys with an

apparatus discharging electric shocks to be applied on camels to induce greater

speed. The committee forbids the use of such devices. Those found possessing it

in the races will be disqualified and the apparatus will be confiscated."6

Return to Index

The detailed description of the organizational aspects of camel racing in the

UAE has shed light on the scope and significance of the economic dimension of

this whole national cultural industry, and therefore my notes on economic

aspects will be brief. As stated earlier, the emergence of this camel phenomenon

needs to be understood within the broad context of the oil economy and the

building of the modern nation-state that has generated multiple transformations

in the society at large.

During the initial phase of the oil boom traditional economic activities

collapsed relatively quickly. Traditional pastoralism, on which the camels

totally depended, was not an exception. Camels were margina1ized, as old Bedu

pastoralists were attracted to easier jobs, better salaries, and a more

comfortable existence in towns or newly built village communities. However, they

remained feeling ill at ease in the rapidly changing oil world. In the

mid-seventies their views and sentiments about the increasing loss of their

camels, which represented their traditional wealth and repertoire of traditional

skills, symbols, and meanings, were voiced to their ruling shaikhs. In one

television interview with Shaikh Zayed he stated his reply to his complaining

camel tribesmen, "Give us some time to think of ways and approaches to do

something about this deteriorating camel situation." Informants love to

quote Shaikh Zayed saying to his Bedu tribesmen, "Look after your camels

well. A day will come when they will be worth millions." While this

statement was put in a rather prophetic form, it is not now too far from

reality. Shaikh Zayed in a 1997 TV program gave many reasons for the increasing

attention to camels. One of them was the statement that " . . . we are in

debt to camels. Therefore we are obliged to protect them and those who grew up

with them. Protecting the camels (al hejin) means providing material benefits

and interests for their owners."

The Canadian anthropologist Louise Sweet in a 1970 article explained that

camel raiding among the North Arabian Bedouins was essentially "a mechanism

of ecological adaptation." Bedouin groups when hungry and in need raided

each other on the backs of their agile hejin to capture wealth; thus she viewed

raiding as a suitable strategy, a functionally adaptive mechanism within the

context of the constantly changing desert ecology. Raiding was, in economic

tenI1S, a strategy, a war sport in order to keep camel wealth circulating among

groups which often competed and warred with each other over scarce desert

resources. Transferring this theoretical notion to viewing camels racing with

and against each other within the new context of the oil economy is quite

attractive. It offers a plausible explanation to see these thousands of camels

racing against each other on the track as a way of capturing some of the new and

abundant oil wealth. As some Bedu say, "Once you get into that camel ring

you cannot get out of it."7

It is understandable why it becomes difficult to get away from such a

"ring," as the stakes are quite large. In economic terms, the racing

ring becomes the field through which, as far as camel breeders are concerned,

one can get to the lavish and abundant bounty of the oil state. During the long

racing season the ring and the multiple little and not-so-little economic fields

which grow around it offer rich pasture land, so to speak, where running camels

and their owners can forage in the new terrain of oil ecology which is now

governed by rules and methods of its own.

This kind of analytical explanation becomes more plausible when we recall the

specifics of the political economy of the oil state (dawlat al naft) in

the Gulf. As a type of polity and governance the oil state is characterized by

having a hereditary shaikhly ruling family in control of both power and

executive authority of a growing state structure. The right of rule of the

shaikhly dynastic families, who are linked to notable tribal origins, is still

partly legitimized by shared beliefs in old values and political traditions. The

state controls and manages both the production and marketing of oil. Therefore,

because of this privileged role and through the executive power in the hands of

its shaikhs or emirs, the state controls "the means of allocation" of

wealth in society (Ismail 1982). As a result the state is given a uniquely

powerful role in society; it is the largest and most powerful employer. In the

UAE over 95% of all employed nationals work in the state public sector (Al Faris

1996).

As an embodiment of political society, the oil state nowadays dominates

"civil society" in exaggerated form (Khalaf and Hammoud 1988: 351).

The fact that the state relies primarily on autonomous sources of income (oil

revenues) means that it has become, in economic terms, disarticulated from its

underlying population. This emergent structural economic disarticulation between

the state and its population is not mirrored in other areas of socioeconomic

life. The distribution of oil wealth has in a sense helped the state to come

closer to its small communities. This has been achieved through the ruler's

economic capacity and commitment to modernize state and society. Modernization

has meant that the state became primarily engaged in the distribution of oil

wealth among its very small population. This has been achieved through four main

channels: a) modernizing state political infrastruture, that is, building state

departments and agencies; b) building extensive public works and myriad social

welfare institutions which provide free welfare services and provisions; c) an

open-door policy for employing its citizens within the still burgeoning state

and welfare institutions; and d) offering extensive economic help to nationals

to start their own small businesses which they manage while still maintaining

their public jobs.

In view of the above, it is not surprising that this emerging type of welfare

state, personified by the ruling shaikhly dynasties, has produced in the eyes of

its underlying small population an image of a paternalistic, all-omnipotent,

all-providing, all-generous giving father. In economico-political terms we can

therefore understand why the Bedu camel breeders, when talking about their

present conditions, raise their hands and tongues in praise to Allah and their

shaikhs. The phenomenon of heritage revival, such as the building and continuous

modernization of camel racetracks, becomes in itself an avenue for distributing

wealth among the camel people and far beyond. This same economic process can be

seen in the revival of other traditional economic activities, like the building

of old traditional pearling boats, sailing boat races, pearl diving, the

construction of several heritage villages, and so forth.

The significant point that needs to be noted here is that the role of camels

within the new context of the oil state has been transformed, on the surface at

least, from the realm of economy to that of culture. Having said that, we should

immediately reaffirm that the production of camel racing as a cultural sport has

many economic underpinnings. The Bedu are fully aware of the importance of these

economic dynamics which support the reproduction of camel races as cultural

festive spectacles, and which manifest themselves ill numerous areas.

Return to Index

The dynastic shaikhly ruling families in the emirates, like Al Nahyan of Abu

Dhabi and Al Maktoum of Dubai, are quite large, and most members are involved

now in owning fine racing camels that they entrust to Bedu camel breeders as

their trainers. According to informed sources, it is estimated that the three

senior brothers of Al Maktoum family own around 15,000 camels, and around one

third of this number is used for breeding racing camels. Shaikh Mohammed alone

has more than 30 trainers. We can estimate the large numbers of Bedu mudhamers

employed by them, particularly when it is known that camel farms range in size

from 6 to 100 camels, some being even larger. It should be remembered that the

shaikhly ruling families are quite large. Among them the ownership of fine

racing camels has indeed become a contagious and popular socio-cultural

activity.

Shaikh Zayed, President of the UAE, and his eldest son, Shaikh Khalifa have

both established scientific centers for breeding racing camels on the outskirts

of Al Ain City. Several camel specialists, immunologists, and laboratory

research assistants have been recruited from places as far away as Australia to

staff these centers, which are equipped with elaborate technologies for training

camels in gymnasium-like settings that include a camel swimming pool. The

financial management of Shaikh Zayed's and Shaikh Khalifa's camel farms is done

through a special department known as Al Da'era Al Khassa, The Private

Department of His Highness The President of the State and HRH, The Crown Prince.

It is a large 2-floored building located in Al Ain City, and has around 100

employees who manage the monthly expenditure of 25 million dirhams (U.S.$6.2

million). This money is spent not only on camel farms but also on agricultural

farms and palaces as well as their private guards, known locally as al

medharzeya. The mudhamers in the shaikhs' camel farms receive around DH

10,000 as a monthly salary, which is adequate to support the large families

usually still found among Bedu tribesmen. Many of them have supplementary income

derived from small commercial enterprises, and some breed racing camels of their

own for both Facing and/or selling in the market for the highest offer. The

mudhamer is given a four-wheel drive car, a water tank truck, a mobile phone,

and a walkie-talkie radio that he uses to give instructions to the jockey during